Kosovo

by William Dorich

Kosovo

by William Dorich

|

|

Thomas Emmert

Prologue to Kosovo:

The Era of Prince Lazar

There is a lovely stone monastery in a lonely, wooded river valley of Serbia about halfway between the northern border with Hungary and the southern border with Greece. Today, like 603 years ago, it is not terribly convenient to get to this place called Ravanica. A train from Belgrade disgorges its monastic pilgrims in the small town of Cuprija on the banks of the Morava River. In Roman times the site of this town was occupied by a fortified civil settlement called Horeum; and in the early medieval period the town gained the name Ravno or flat, and it was here in 1189 that envoys of the Serbian ruler Stefan Nemanje and the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa met as the German emperor and his forces passed through the area on their way to the Third Crusade. In the second half of the 17th century the town acquired its present name of Cuprija when Grand Vizier Mehmed Pasha Cuprilovic had a bridge (cuprija in Turkish) built across the Morava on the site of the former Roman bridge. Cuprija was the center of an administrative district during

Turkish times.

There is a lovely stone monastery in a lonely, wooded river valley of Serbia about halfway between the northern border with Hungary and the southern border with Greece. Today, like 603 years ago, it is not terribly convenient to get to this place called Ravanica. A train from Belgrade disgorges its monastic pilgrims in the small town of Cuprija on the banks of the Morava River. In Roman times the site of this town was occupied by a fortified civil settlement called Horeum; and in the early medieval period the town gained the name Ravno or flat, and it was here in 1189 that envoys of the Serbian ruler Stefan Nemanje and the German Emperor Frederick Barbarossa met as the German emperor and his forces passed through the area on their way to the Third Crusade. In the second half of the 17th century the town acquired its present name of Cuprija when Grand Vizier Mehmed Pasha Cuprilovic had a bridge (cuprija in Turkish) built across the Morava on the site of the former Roman bridge. Cuprija was the center of an administrative district during

Turkish times.

It is the spring of 1390 and the slow, mournful procession is carrying the perfectly preserved body of Lazar Hrebeljanovic, the Serbian prince who had been killed by the Ottoman Turks the previous summer during a battle on the Field of Kosovo. Myrrh emanates from the holy remains.

Today, if you are lucky, you may find a private car to take you along the dusty road some 11 kilometers to the Monastery of Ravanica. If not, the walk is long enough to serve as a kind of time machine in which you can begin to imagine the procession that moved along the same dusty road more than 600 years ago.

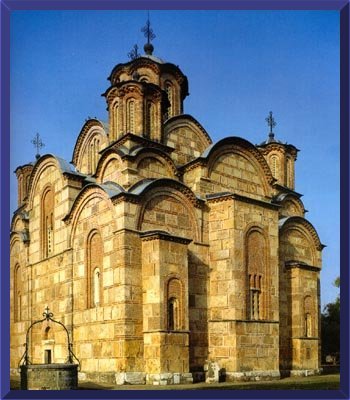

The monastery with its fortifications and church was built by Prince Lazar only a short time before the battle of 1389. The church was one of the first examples of a new architectural style that would continue to enrich the countryside of Serbia for the next half century. Here the holy relics of Saint Lazar of Serbia would rest for some 300 years through Turkish conquest and subsequent wars, famine, plague, and numerous fires.

The principality of Lazar Hrebeljanovic represented only a relatively small part of the medieval state of Serbia, which achieved its greatest territorial extent in the early part of the 14th century. A little more than 30 years before the Battle of Kosovo, Serbia was a powerful empire which controlled almost two-thirds of the Balkan peninsula and threatened to conquer Byzantium itself. It had begun its quest for independence and Balkan power in the mercurial atmosphere of the late 12th century. Throughout most of that century the Serbian leaders, or great zupans as they were called, had been forced to recognize the suzerainty of the Byzantine Empire. After 1180, however, upon the death of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus, the relatively small territory of Rascia (the eastern Serbian lands) began to expand into the land surrounding it, including today's Montenegro and Kosovo. Under the rule of Stefan Nemanja, the founder of a new dynasty for Serbia, this new state continued to struggle with the Byzantine Empire and to recognize its authority, but the dominance of the Greeks in this region of the Balkans was clearly over. Under the leadership of Stefan Nemanja's son, Stefan the First Crowned (1196-1217), Serbia became an independent kingdom with an autocephalous Church.

Stefan received his crown from a papal legate in 1217. The autocephalous archbishopric, on the other hand, was established with the blessing of the Byzantine emperor, who at the time was in exile in Nicaea. Serbia thus found herself as a pawn and a willing benefactor in the continuing rivalry between Constantinople and Rome. The establishment of a kingdom and an independent Church gave the land a certain legitimacy in the eyes of other European states, and it encouraged within Serbia a new respect for the authority of the Nemanjic dynasty. According to the political ideology of the Byzantine world, the ideal state achieved a working harmony between the 2 heads of the body politic, the sacred and the secular. Throughout the growth and decline of the Serbian medieval state, the Serbian Church accepted this responsibility and became a powerful force, helping to build and then preserve a sense of Serbian historical consciousness.

These important developments encouraged a solid foundation for the internal growth and outward expansion that occurred in Serbia during the 13th century. This beginning period of Serbia's ascendancy was a particularly volatile time in the Balkan peninsula. With the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and the conquest of Constantinople by Western Christians, Serbia found itself surrounded by a number of new hostile states. Leadership in the region continually changed hands, and the struggle for dominance was only complicated by the invasion of the Mongols in 1241 and the reconquest of Constantinople by the Greeks in 1261.

Serbia managed to survive the turbulent conflicts of the first part of the century and found itself taking control in the peninsula by the end of the century. Under the rule of Stefan Uros II Milutin (1282-1321) Serbia advanced into northern Macedonia. His son, Stefan Uros III Decanski (1321-1331), extended Serbian dominion over most of the Vardar Valley; and his grandson, Stefan Dusan, pushed his armies all the way to the Gulf of Corinth. Serbia's greatest success in territorial aggrandizement was largely due to the effort and vision of Dusan. He was an ambitious leader who planned to conquer all of Byzantium and to establish a Serbo-Greek Empire in the spirit and tradition of the Byzantine Empire. The entire course of his 25 years as king and emperor (1331-1355) was dominated by this grandiose objective.

Dusan's era was the grand moment in Serbian history. He patterned his court after Byzantium, introduced an efficient system of administration, codified the law, developed communications, and brought in experts from all over Europe to help advance the state. In 1346 he proclaimed himself emperor of the Serbs and Greeks, of Bulgars and Albanians. Crowned by the archbishop of Pec, he then raised the archbishop to the rank of patriarch. By 1355 he had been successful enough to consider a move against Constantinople itself with the idea of supplanting the Greek Empire with a Serbo-Greek hybrid. However, he died on his way to the imperial city.

His death was a disaster for the Balkans. Long before anyone else, he had begun to understand the potential danger posed by the presence at

his southern border of a new force: the Ottoman Turks. In 1354 he sent his emissaries to Pope Innocent IV in Avignon with the request that he be named the captain of a crusade against the Turks.

He asked the pope to send his legates to Serbia in order to arrange the agreement. In exchange for the pope's support Dusan was prepared to recognize the pope as father of Christendom, successor of Peter, and representative of Christ; he also vowed to promote peace and friendly intercourse between the Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox in his realm. The pope was interested, but then Hungary, supposedly the defender of Western Christianity in the Balkans, attacked Serbia. Shortly after, the negotiations between Rome and Serbia ended.

The Serbian Empire fell apart quite quickly. During the years of the reign of the last Nemanjic emperor, Uros VI, the authority which the Nemanjic dynasty represented was completely undermined by those powerful lords who succeeded in governing their territories quite independently of their emperor. In the 1360s the center of power in Serbia gravitated first to the western territories of Vojislav Vojinovic, and after his death in 1363 to Macedonia and the lands of Jovan Ugljesa and, more importantly, his brother, Vukasin.

Vukasin became king of Serbia and co-ruler with Tsar Uros VI. Uros, who was childless and had no success in maintaining central authority in the short-lived Serbian Empire, apparently recognized in Vukasin his own successor. Vukasin, in turn, designated his son, Marko, as "young king," in anticipation of the foundation of a new dynasty. By 1371, the erosion of Uros' power throughout the empire was complete, and formally Vukasin was the only real authority. He and his brother, Despot Jovan Ugljesa, governed an enormous territory in Macedonia and Thrace and certainly represented the strongest Christian power in the Balkans. But the process of feudalization in Dusan's former empire had progressed long enough so that few important territorial lords recognized the authority of Vukasin. And the two most prominent Serbian lords north of Macedonia, Lazar Hrebeljanovic and Nikola Altomanovic, demonstrated no loyalty to the king. Whether time would have favored a restoration of the Serbian state by Vukasin and his son Marko can never be known. In September 1371 the king and his brother died while defending Ugljesa's territories against the Turks on the river Marica. A short time later Tsar Uros died, and in the 18 years which separated his death from the Battle of Kosovo the struggle for territorial aggrandizement continued among the nobility in Serbia.

With Macedonia in Turkish hands, the center of this struggle moved north and northwest to the territories of Nikola Altomanovic, Lazar Hrebeljanovic, and Tvrtko Kotromanic. Altomanovic began his rise to prominence after the death of his uncle, Vojislav Vojinovic. His conquest of Vojinovic's lands started in 1367, and within a year his province stretched from Rudnik to Kosovo and the sea. He controlled most of the river basin of the Drina, governed Dracevica, Konavlje, and Trebinje, and for a shorter time occupied the coastal region from the Bay of Kotor to Ston; excepting, of course, the territorial ambitions of the Serbian Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic and the Bosnian Ban Tvrtko Kotromanic. Lazar lost the vital mining center of Rudnik to Nikola sometime at the end of 1371 or the beginning of 1372, and was involved in frequent border skirmishes with him. Tvrtko had watched Altomanovic establish himself along Bosnia's entire eastern border and now was especially threatened in those areas of Hum which he held. A mutual desire to eliminate this menace from their borders and to acquire new territories in the process brought Lazar and Tvrtko together.

Their campaign against Altomanovic took place in the autumn of 1373 with assistance from the king of Hungary; and in a very short time Altomanovic was defeated, captured, and blinded. The elimination of Altomanovic from the competition for territory and authority in post-Nemanja Serbia left only Prince Lazar and Ban Tvrtko as the most powerful contenders. Tvrtko, a distant relative of the Nemanjici, was in control of enough Serbian territory by 1377 to justify (at least in his mind) his coronation as "king of Serbia, Bosnia, the Pomorje, and the western lands." Venice, Dubrovnik, and even Hungary recognized Tvrtko as "rex Rassie," and it appears that Prince Lazar and his son-in-law, Vuk Brankovic, at least approved of Tvrtko's coronation. Whether they actually accepted him as their lord and king, however, seems highly unlikely. Regardless of Tvrtko's pretensions to the Serbian throne, it was really Prince Lazar who was quickly becoming the dominant figure in post-Nemanja Serbia. If his state eventually represented the only hope in the peninsula in the struggle against the Turks, it was not an unrealistic hope given the increasing strength and prestige of the principality and its prince. Lazar was setting the stage for the restoration of central authority in Serbia, and his court at Krusevac was becoming a lively intellectual and artistic center in the Balkans.

Lazar Hrebeljanovic, the martyr of Kosovo, became independent during those years in which the Mrnjavcevic brothers dominated the political scene in Serbia. Unfortunately, very little is known about his early life. His bastina (hereditary land holding) was probably located near his birthplace of Prilepac, which was east of Kosovo in the vicinity of the important mining center of Novo Brdo. Pribac, his father, was a logothete at the court of Emperor Dusan, and medieval sources say that it was at Dusan's court that Lazar was educated.

He began his career with a low-ranking noble title in the Serbia of Tsar Dusan. By 1362 he appeared to be a man of some influence at the court of Tsar Uros, and in 1371 he is referred to for the first time in extant sources as "prince." It is not known when Tsar Uros awarded Lazar the title of prince; but it seems quite clear that, in spite of some territorial acquisitions following the Marica Battle, Lazar's real success only began after Altomanovic's defeat.

The victory over Altomanovic allowed Lazar to reconquer Rudnik, which Altomanovic had taken shortly after the battle on the Marica, and to seize all the territory in the area of the Western Morava River, including the town of Uzice. He did have to pay for his victory over Nikola by surrendering his independence to King Louis of Hungary and temporarily ending his expansion to the north, but his relationship to King Louis was no real obstacle to his authority in Serbia.

Lazar devoted a great effort in the early years of the 1370s to consolidating his authority in the northern regions of Serbia and to creating the structure of a strong and unified principality. His decision to build his court city in the north, away from the heartland of Nemanjic Serbia, was a necessary one. After the battle on the Marica almost everything south and east of Kosovo was under Turkish authority. His new court in Krusevac, however, was a comfortable distance from the Turks. It was located at the mouth of the Rasina River where it enters the Western Morava about 14 kilometers west of the Southern Morava; and, although it was not far from the important Belgrade-Constantinople highway, it was still quite isolated. Lazar built his fortress above an already existing settlement. The exact date of its construction is impossible to determine, but it was begun sometime after 1371, and by 1377 it was already an established center.

This was the "Morava period" of Serbian art and architecture. Lazar dotted his lands with churches and monasteries and made them financially strong by showering them with rich landed estates. Ravanica was given more land (148 villages) than any monastery during the entire era of the Nemanjici.

The growing political and cultural strength of Lazar' s principality certainly depended on adequate economic resources. The two most important mineral centers in Serbia (Rudnik and Novo Brdo) were both under Lazar' s jurisdiction; and it was the wealth of these mines which created the economic basis of his power. Ravanica alone was given 150 liters of silver each year by Prince Lazar.

Lazar' s success, however, was not due only to territorial aggrandizement and economic power. The support of the Serbian Church was a most essential ingredient in Lazar' s efforts to end the schism with Byzantium. That schism had existed since 1346, when Byzantium placed Serbia under anathema after the emperor of Serbia had proclaimed an independent patriarchate in Serbia. Lazar' s lands continued to bear the sting of that anathema. In 1375, however, due to the efforts of Prince Lazar and Isaiah, the Serbian prior of the Russian Monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mount Athos, the schism was ended and Byzantium formally recognized the legality of the Serbian patriarchate. This was perhaps Lazar' s most important accom-plishment during the 1370' s, and in itself reserved for him an honored place among his own contemporaries and in history.

As one of the last Christian refuges in the Balkans, Lazar' s principality began to attract large numbers of priests, monks, writers, architects, and artists from Bulgarian, Greek, and southern Serbian areas, which were already subject to the Turks. Travelers report as late as the early 14th century that the area had been empty land, unsettled, with thick forests. After 1371, however, thousands made their way there, including many monks from Mount Athos. They built churches and monasteries and reformed the liturgy. A new era of culture began to flourish in Serbia, which was to reach its fullest expression during the reign of Lazar' s son, Despot Stefan Lazarevic.

There is some disagreement concerning the exact circumstances which led to the reconciliation. The monk Isaiah was a most influential figure at the court of Prince Lazar; he was called on for delicate diplomatic missions. Isaiah' s biographer, who was also a monk on Mount Athos, says that the entire undertaking was in Isaiah' s hands. Constantine the Philosopher, however, who wrote a biography of Lazar' s son in about 1431, attributes the successful reconciliation directly to Prince Lazar. He says that once Lazar had consolidated his authority throughout the principality, the matter of rapprochement between Churches became his chief concern.

In the anonymous biography of Patriarch Sava IV, written in the late 1370s, both Lazar and Isaiah are portrayed as being intimately involved in bringing about reconciliation. The writer says that Isaiah came to Lazar in Serbia to discuss the Church' s problems and to encourage the prince to work for a settlement with Byzantium. Lazar responded by sending Isaiah to Patriarch Sava in Pec, who opposed the idea at first but eventually agreed to support it. In the end, the patriarch himself actually asked Isaiah to go to Constantinople to arrange the agreement. Isaiah returned to Lazar' s court, where he was given everything he needed for the trip. He chose his associates for the mission and then "reported to the whole council, to the old Empress Jelisaveta, and to all the nobles."

The participation of the council and nobility in the negotiations is also mentioned in the biography of Patriarch Ephrem, Sava' s successor. Bishop Marko, the author of this biography written during the first decade of the 15th century, says that Lazar could not bear to see the schism continue between the Churches and, therefore, after consultation with his council and nobility, chose Isaiah and a priest named Nicodemus to go to Constantinople to arrange the peace.

It is clear that no matter how important a role Isaiah may have played in the negotiations which finally resulted in peace, there could have been no agreement without Lazar' s participation in this matter. The support of secular authority was a necessary prerequisite to any successful agreement. Moreover, Lazar himself stood to gain from a rapprochement between the Churches. The ideal ruler in medieval Serbia was expected to demonstrate deep concern for the religious life of his people. Certainly, Lazar' s efforts toward reconciliation with Byzantium would contribute substantially to his own prestige among his subjects.

According to Patriarch Sava' s biographer, the negotiations in Constantinople were successful and the Greeks recognized the legality of the Serbian patriarchate. There was only one condition to the agreement. If at any time the Serbs succeeded in conquering any Greek territory again, they were prohibited from replacing Greek metropolitans with Serbs as Dusan had done. As a sign of the agreement, the Byzantine Patriarch Philotheus, sent 2 representatives to Serbia who celebrated a service of unification in the Church of the Holy Archangels near Prizren and, over the grave of Emperor Dusan in that church, proclaimed the removal of the anathema of Serbia and peace between the Churches.

Patriarch Sava IV died the same year that this peace was concluded, and the choice of his successor did not prove to be a simple matter. Prince Lazar and Djuradj Balsic assembled a council in Pec in October 1375 to elect a new patriarch. The proceedings of that council clearly mirrored the general political disunity in Serbia. Each important territorial lord sought to elect a man from his own territory who would support his own particular interests. They finally chose an elderly ascetic named Jephrem, who represented absolutely no threat to any of the individual lords and apparently had the support of the Byzantine and Serbian patriarchates. Nevertheless, Jephrem had accepted the position very reluctantly, and in 1379 he returned to his less demanding life as a monk.

Lazar' s role in this final chapter of rapprochement between the Byzantine and Serbian Churches assured him the support of the Church and its recognition of him as the ruler of Serbia after 1375 and the successor to the tradition of the Nemanjici. Certainly, some of the evidence for the Church' s relationship with Lazar comes from the panegyrics of the post-Kosovo period, which did not hesitate to embellish the details of Lazar' s life and work; nevertheless, there is little reason to doubt that the Church did recognize him as the autocrat of Serbia in the decade preceding the Battle of Kosovo.

Whether that recognition extended beyond the circle of the Church, however, is a more difficult question. Lazar did identify himself as autocrat of Serbia in several charters. Not long after a successful military adventure in 1379 to the north against Radic Brankovic, the lord of Branicevo and Kosovo, Lazar issued a charter in which he referred to himself as "Stefan Prince Lazar, pious and autocratic lord of Serbia and the Danubian lands." In still another charter he wrote: "I, pious Prince Lazar, autocrat of all Serbian lands." But Lazar was not the only territorial lord to identify himself as "autocrat." After the collapse of the empire, various individuals used the term in order to express the fact that they considered themselves independent. And the name "Stefan," although a symbol of state authority during the time of the Nemanjici, was also adopted by Tvrtko when he proclaimed himself king of Serbia and Bosnia.

We may also ask whether Lazar would have retained the modest title of prince if his pretensions had been more grandiose or his authority more widely recognized. The reality of the political situation in Serbia was that there were many Serbian territories which were not under his authority. The Balsici ruled in Zeta; Vuk Brankovic was lord of Kosovo and the surrounding regions; and King Tvrtko maintained his control over a significant amount of Serbian territory. The very fact that Tvrtko and Lazar remained friends and allies would seem to indicate that Lazar represented no threat to Tvrtko's own pretensions. Dubrovnik never referred to Lazar as prince of Serbia, but only as comes Lacarus or simply Lacaro.

This is not to deny the position that Lazar began to enjoy in the decade before Kosovo. Although his principality had less than one-fourth of the territory of Dusan's empire, he was still the most powerful of those Serbian lords who were not subject to the Turks. He united the central regions of Serbia with those northern provinces of Macva, Kucevo, and Branicevo, which the Nemanjici had held only briefly. He enjoyed the homage of a number of vassals on his territory, and his lands became a haven for those fleeing the Turks in the south. As the Turkish threat increased, he sought alliances with lords in neighboring territories by offering his own daughters in marriage. His sons-in-law included Nikola Gorjanski, the ban of Macva; Djuradj Stracimirovic Balsic, lord of Zeta after 1385; Vuk Brankovic; and Alexander, the son of Ivan Sisman, emperor of Bulgaria. It was this familial relationship that led Jirecek to argue that although Lazar was not the autocrat of all Serbia, he was the head of a family alliance.

The precise nature of the relationship within this alliance is not easy to determine. There is little question about Balsic's independence. In

a charter of 1386 he proclaimed: "I, Balsic in Christ the Lord, Djuradj, pious and autocratic lord of the lands of Zeta and the coast." Brankovic's independence is less obvious and more difficult to determine. By 1379, he was in control of extensive territory which included Pristina, Vucitrn, Trepca, Zvecan, Pec, Prizren, Skoplje, and Sjenica. Nevertheless, he never referred to himself as autocrat or autocratic lord as did Lazar and Djuradj. A number of scholars have argued on the basis of certain fragmentary evidence that Vuk Brankovic was not independent at all but rather recognized Lazar as his sovereign. One might assume that this is a clear indication of some type of subordinate relationship. Understood in a larger context, however, it may be nothing more than an expression of Vuk's respect for his father-in-law - the pater familias, as Jirecek would have it.

Evidence from sources outside of Serbian territory would seem to corroborate the conclusion that Lazar was not recognized (at least outside the narrow circle of the Serbian Church) as autocrat of all Serbia. When the Republic of Dubrovnik solicited guarantees of its old trade agreements with Serbia, it did so not only with Lazar but also with Djuradj Stracimirovic Balsic and with Vuk Brankovic. If Lazar had been recognized by the republic as sovereign of Serbia, only he would have confirmed these trade agreements.

In 1388 a similar situation occurred. Every year Serbian monks from the Monastery of the Archangels in Jerusalem came to Dubrovnik to receive the Tribute of Ston'a sum of 500 perpers which had been presented by the republic to these monks each Easter since 1333. It was the custom for Dusan, and later Uros, to provide Dubrovnik with a letter of faith on behalf of these monks. In 1388, however, Lazar, Vuk, and Djuradj all presented individual letters of faith to Dubrovnik in which they requested prompt payment of the tribute to the travelers from Jerusalem. Although Lazar may have been the strongest territorial lord in the remnants of imperial territory, it appears his sovereignty was largely confined to the lands of his own principality and perhaps to those of his son-in-law, Vuk Brankovic.

Whatever the question of Lazar's authority, however, everything changed with the tragic conflict on Kosovo in June 1389. Serbia was not very strong when the attack came. She lost her prince and the flower of her nobility in the battle; and the following year Lazar's widow had to accept a tribute relationship with the Ottomans. Conscious of the need to combat an understandable pessimism of their people, Serbian monks wrote eulogies, liturgical and hagiographic works in which they celebrated the martyrdom of their prince and interpreted the battle and the eventual loss of independence as a kind of martyrdom for the whole Serbian people, a martyrdom expected by God and freely accepted by those who died. Having chosen them as the "new Israel," God would eventually return Serbia to them. A cult of the martyred prince was encouraged by these writings. It joined the other 2 cults of the Serbs, 1 devoted to Stefan Nemanjic, who founded the first unified Serbian state in the late 12th century, and the other to his brother, Sava, who established the first autocephalous Serbian Church in the early years of the 13th century. Like these 2, Lazar would become a saint in the Serbian Church.

Others believe that there was probably a formal canonization and that the rite of canonization took place at the time that Lazar's remains were moved from Pristina to Ravanica sometime in 1390 or 1391. In the Narration on Prince Lazar by Patriarch Danilo III we read that the decision to transfer the relics was made by Lazar's children. Stefan and his brother Vuk pointed out to their mother that it was shameful that the relics of their father were not preserved in the Church of Ravanica. Milica granted their request, and eventually the transference was carried out with the blessing and under the direction of the hierarchy of the Serbian Church.

Unfortunately, the patriarch gives no information about any ceremony of canonization. Rade Mihaljcic has argued that there are a number of things, however, which suggest that there probably was a formal canonization: first of all, Patriarch Danilo who organized the transference of Lazar's remains was familiar with the rite of canonization which was used for Simeon Nemanja; secondly, the most important heads of the Serbian Church participated in the transference; and, thirdly, several contemporary sources report that Lazar's body was in perfect condition when it was exhumed in Pristina and that it exuded the fragrance of myrrh. An incorruptible body and the emanation of myrrh were often seen as clear signs of saintliness. Finally, Mihaljcic points out that the relatively large number of cult texts devoted to Lazar, as well as their early appearance shortly after the transference of the prince's relics, suggest an organized cult rather than one which developed spontaneously.

Lazar was the first secular figure to become a saint in Serbia after 200 years of the Nemanjici.32 This perhaps helps us to understand the concern of his eulogists to emphasize the family ties between Lazar and the "saintly-born" dynasty of the Nemanjici. If Prince Lazar could be viewed as part of a continuous line of authority that had begun with the Nemanjici and that would continue after Lazar, it might be possible to overcome the sense of disorder and chaos which had characterized the troubled years 1355-1389. These writers wanted to see their own society as an integral part of the Nemanjic tradition. In giving legitimacy to Lazar, they sought to identify Lazar's Serbia and Nemanjic Serbia as one and the same entity.

Lazar's martyrdom on Kosovo was Serbia's Golgotha, but his second burial in Ravanica and his canonization reminded the faithful of the hope of resurrection. One day Serbia would be whole again. The agony of defeat became the symbol of the purest victory.

It appears that Lazar became a saint soon after his martyrdom on Kosovo. Some have suggested that the very act of martyrdom itself guaranteed him sainthood, and thus a spontaneous cult emerged among the survivors of Kosovo.

|