Kosovo

by William Dorich

Kosovo

by William Dorich

|

|

Alex Dragnich and Slavko Todorovich

The Serbian Revolution and Albanians

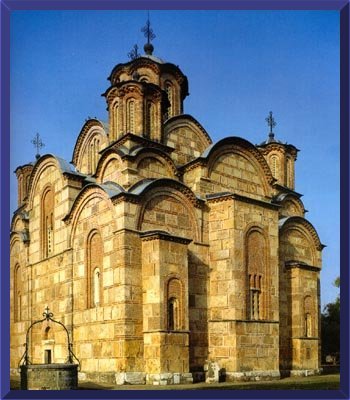

At the beginning of the 19th century the Balkan peninsula was a "powder keg," and Serbia with its uprisings (1804 and 1815) was the "fuse." The Serbs were soaring upward, carried on the wings of national liberation, and the Greeks were not far behind. The Albanians, pulled down by the weight of the aging Ottoman Empire, nevertheless realized that the Serbs and Greeks could not be held down. Should they try to stop the Serbs or should they join them and turn against Constantinople? They were undecided.

To the Serbs, the uprising under their peasant leader, "Black George" (Karadjordje), was a repeat performance of what the Serbs did under Nemanja some several long centuries earlier. They realized that with the "sick man" in Constantinople the moment for the leap to independence was at hand. But to the Albanians any "leap" would have had to be out of Constantinople, where they were providing honor guards for the sultan and performing many administrative tasks. The Serbs were in their days of genesis; the Albanians felt carried by the flood of a terminal deluge. Would the 2 nations, which earlier had had difficulty finding a common language, be able to join hands now? The Great Powers, for different reasons, were not interested in having Albanians and Serbs living in peace. Austria wanted to build an Albanian wall between the Serbs and Montenegrins that would prevent their unification. Italy did not want more Slavs in the region of "mare nostrum." Turks wanted to have a Muslim foothold against Austria's southern expansion. Russia was interested in exploiting the Balkan situation so that it could open a second front, if necessary, in its wars against Turkey. The Vatican wanted to complete its long-term task of pushing Orthodoxy out of the littoral. For the Balkan "pawns" it was difficult, if not impossible, to bridge the abyss and resist being sucked into the whirlpool.

To the Serbs, the uprising under their peasant leader, "Black George" (Karadjordje), was a repeat performance of what the Serbs did under Nemanja some several long centuries earlier. They realized that with the "sick man" in Constantinople the moment for the leap to independence was at hand. But to the Albanians any "leap" would have had to be out of Constantinople, where they were providing honor guards for the sultan and performing many administrative tasks. The Serbs were in their days of genesis; the Albanians felt carried by the flood of a terminal deluge. Would the 2 nations, which earlier had had difficulty finding a common language, be able to join hands now? The Great Powers, for different reasons, were not interested in having Albanians and Serbs living in peace. Austria wanted to build an Albanian wall between the Serbs and Montenegrins that would prevent their unification. Italy did not want more Slavs in the region of "mare nostrum." Turks wanted to have a Muslim foothold against Austria's southern expansion. Russia was interested in exploiting the Balkan situation so that it could open a second front, if necessary, in its wars against Turkey. The Vatican wanted to complete its long-term task of pushing Orthodoxy out of the littoral. For the Balkan "pawns" it was difficult, if not impossible, to bridge the abyss and resist being sucked into the whirlpool.

In the early part of the 19th century both Montenegrins and northern Albanians had their sights fixed on what was happening to the north. For 9 crucial years the Serbs battled the Turkish armies (1804-1813), and only two years later after being "pacified" they rose again. These 2 open insurrections sent shock waves throughout the Balkans and central Europe, Leopold Ranke, a German historian, published a book about these uprisings under the title Die Serbische Revolution (1829). "The Serbian Homer," as he liked to call himself, wrote about the "seeds" that were sown, which raised many eyebrows from Petersburg to London. In those capitals, the "Eastern Question" was now compounded by the "Serbian Question," an unknown factor in international diplomacy.

Overnight, the Serbs got a taste of international politics. The Russians sent a message to their Slav brothers: Just think what you and we can achieve together. To the delight of Karadjordje, a Russian general arrived at the Serbian front with a token force of 1,000 troops. The battle of Shtubik (1807) was their first common military victory against the Turks. But after Austerlitz, as Napoleon tied the hands of the Russians (Peace of Tilsit), the Serbs were left alone to face the onrushing Muslims. Black George was furious at the Russians and their representative in Belgrade, Rodofinikin, found it advisable to remove himself temporarily from the city by crossing the river to the Austrian town of Zemun. In 1810, Karadjordje sent his delegate, Rado Vucinic, to Napoleon, who gave him a cold shoulder. In 1813, Karadjordje crossed the river himself as Serbia's dream was crushed.

Nevertheless, in the popular mind, Karadjordje came to be viewed as the avenger of the Serb's defeat at Kosovo. As the courageous leader of the Serbs? First Uprising that was to lead to Serbia's resurrection, he became and remained a Serbian hero, a sort of Serbian George Washington.

It was not any easier for the leader of the Second Uprising (1815), Milos Obrenovic. He gathered his peasant "elite" in Takovo and told

them it would be tough going. He insisted on 1 thing: absolute obedience and a final say in decision making. Since he was the one who got them into the predicament, and who disposed of substantial means, and was the only one who knew the potential of his secret dealings with the Turks, the "elite" had no choice but to agree. Soon he had domestic challenges to his absolutism, and foreign powers gave him a taste of international intrigue. When he went to pay his respects to the sultan (some years after the success of the uprising) whom did he meet at the Bosporus but the Russian ambassador, Buteniev. The sultan gave Milos an expensive saber, a beautiful horse, and 6 artillery guns: the Russian ambassador invited Milos "to lunch on his frigate." The Austrian envoy, not to be outdone, went a step further: he offered, as a token of high recognition, to send "one person with appropriate staff to open an office in Belgrade." Flattered, Milos accepted the offer and informed the sultan, who agreed, and told Buteniev about it, who "said nothing, but just kept his silence."

It was not any easier for the leader of the Second Uprising (1815), Milos Obrenovic. He gathered his peasant "elite" in Takovo and told

them it would be tough going. He insisted on 1 thing: absolute obedience and a final say in decision making. Since he was the one who got them into the predicament, and who disposed of substantial means, and was the only one who knew the potential of his secret dealings with the Turks, the "elite" had no choice but to agree. Soon he had domestic challenges to his absolutism, and foreign powers gave him a taste of international intrigue. When he went to pay his respects to the sultan (some years after the success of the uprising) whom did he meet at the Bosporus but the Russian ambassador, Buteniev. The sultan gave Milos an expensive saber, a beautiful horse, and 6 artillery guns: the Russian ambassador invited Milos "to lunch on his frigate." The Austrian envoy, not to be outdone, went a step further: he offered, as a token of high recognition, to send "one person with appropriate staff to open an office in Belgrade." Flattered, Milos accepted the offer and informed the sultan, who agreed, and told Buteniev about it, who "said nothing, but just kept his silence."

Soon the Austrian consul, Mr. Meanevich, arrived in Belgrade and brought to Milos not 1 but 2 Iron Crosses of the First Order. In no time, the British envoy, "with his personal flag," announced himself. Puzzled, Milos admitted, "I had no idea foreign courts would start sending those counsels." Soon the web of international plots was all over the semi-autonomous Turkish province of Serbia. "Never did I want to get rid of the Russians, so that I could join the British," protested the indignant Milos, "nor is it true that the British ever offered me a million ducats to come over to their side." But Milos suspected that British Consul Hodges was the source of the rumor, because he was "a person of no character and a blabbermouth."

"My greatest mistake," said Milos in his memoirs, "was in allowing the representative of Metternich to come here to open his office ... but, in spite of all the headaches I had with the consuls, I managed continuously to improve the welfare of my province ..."

Milos apparently did not feel that all foreigners were a "headache," as he cultivated relations with Marashli Ali Pasha, the vizier of Belgrade who was delegated by the sultan to formulate the details of Serbia's new status in the Ottoman Empire. In dealing with the sultan's delegate, Milos' most powerful "argument" was a discreet but generous bribing. He looked out for the influential, sometimes anti-government Muslims, mainly those who were willing to compromise their allegiance. In this way, Milos opened one door after another, and obtained what he wanted without spilling the blood of his people.

An Albanian who sought Milos' friendship was the vizier of Skadar, Mustafa Pasha Bushatlija. He maintained that he was a descendant of the old Montenegrin Crnojevic family, and he had dynastic ambitions. He was 1 of 2 mighty Albanian pashas (the other being Ali Pasha of Tepelena) who resisted the central Turkish government of Sultan Mahmud II. Both of them were eyeing Milos' successful tactics, especially since they

wanted what Milos had: a hereditary principality. Montenegro's ruler, Bishop Petar Petrovic-Njegos I was not enthusiastic about Milos'

dealings with Bushatlija, for obvious reasons: the latter's claim to being a Crnojevic descendant would give him some title to Montenegrin lands as well.

Milos clearly grasped the benefits for the Serbian state in any kind of Muslim opposition to Turkish rule. Anyone challenging the power of the Porte could be sure to attract his attention, regardless of motives. The more trouble the Porte faced, the more it would be willing to negotiate with Milos. When through his correspondence with Mustafa, Milos learned that the sultan was requiring Mustafa to send 60,000 Albanians to fight the Russians, Milos advised stalling tactics and avoiding direct confrontation with Russian troops. The Porte knew of Milos' correspondence with Bushatlija through the reports of its own spies, and Milos almost got into trouble as Mustafa was militarily defeated by a Turkish expeditionary force when the Russo-Turkish war was over (1829). Due to Austria's intervention, Mustafa's life was saved and he continued to live in Constantinople.

This experience made Milos even more cautious when another Muslimized Christian, Bosnian Bey Hussein Gradascevic, decided to challenge the authority of the sultan. Hussein came to Kosovo to meet the sultan's troops (July 1831), and defeated the Turkish "pacification" task force. He looked for help from Milos, but Milos did not think Hussein had a chance. Milos was just winning his first battles in diplomacy with the Turks and did not want to risk losing the concessions he had already obtained from the Porte. The following year, Hussein was defeated in a battle near Sarajevo and fled to Austria.

Milos had no use for Albanians (he used the Turkish term Arnauti), and shared the feeling of most Serbs that they were the worst of all the "Turks." First among Milos' priorities was to get rid of all the converted Muslims, whether formerly Serbs or Albanians, as soon as possible. The 2 cities of Cuprija and Aleksinats seem to have been popular with Albanians. Milos was resolute, and through a combination of pressures and fiscal compensation he responded to the pleas of ethnic Turks in Cuprija to help them get rid of the Albanians.

The Serbs made a clear distinction between Turks and Albanians. Turks made up a majority of city dwellers and were landholders or engaged in crafts. The Albanians were a minority and a sort of Muslim proletariat. Both Turks and Serbs referred to Albanians in terms that were usually reserved for the scum of society. They were called "criminals," "brigands," and "murderers," which did not help in restoring social tranquillity and interethnic relations.

In Milos' time Turks were leaving en masse. Being men of property or professional skills, they were not paupers and had somewhere to go - not so the Albanians.

As the 19th century progressed, it became even more evident that the Muslim "aristocracy" in the Balkans was doomed. The more that this was realized the more evident became the gap between the landowners (Turks) and the peasants (Christians). As the peasants liberated themselves from working for Turks, they became individual producers, traded with the cities, and even moved to the cities. Many of them received training in various crafts or otherwise entered commerce. The "Turkish" towns of the Balkans began getting an ever greater segment of Slav professionals. The commercial Christian section began booming, while the Turkish aristocracy wards were decaying as they were losing their material base. Cities like Skoplje, Prilep, Prizren, Ohrid, Bitolj and Solun were attracting dynamic and aggressive Christian (including Greek and Armenian) and Jewish elements.

Economically, the tables were turned against the Turks: in an open society they were losing their land, while in the cities they were not securing for themselves the lucrative prospects of the new capitalism on the march. The Turks sat grumbling, smoking their "chibuks" and drinking coffee, watching Christians taking the initiative. To their dismay, the elegant needle-like minarets were being joined by baroque towers, to them an unbearable sight, spoiling the skyline of "their" Muslim cities.

Albanians, a much more aggressive segment of the Balkan Muslim world, could not just sit by and watch the Christians take over. Yet, they faced a 2-front "war." On the one side were the Serbs, cocky and confident and assertive. On the other front was the Turkish "protector," who dispensed not protection but imposed new restrictions and made new demands and obligations. But Albanians were ill-prepared to stand up to the Serbs and to Constantinople at the same time. They had no central authority to coordinate their actions, no unified ideological philosophy, and no clearly defined national program.

With the passage of time, relations between Serbs and Albanians, instead of becoming more conciliatory, were getting worse. As the Serbian state was growing in size and political importance in Balkan affairs, Albanian fears of "Serbian imperialism" grew apace. Serbia needed its own port on the Adriatic coast, so that it would not have to depend on Austrian goodwill for its economic development. The natural way to this port was through Montenegro. Realizing this, Austria in its 19th century diplomatic efforts, tried with partial success to create a political and military zone between the 2 Serbian states. Albanians were to play a large role in this Austrian scheme. Serbian historian Slobodan Jovanovic says that Albanians had to be "the wall" between the Montenegrins and the Serbs.

In these 2 Serbian states 3 important men were painfully aware of the role assigned to Albania. They were the Montenegrin Prince-Bishop Petar Petrovic-Njegos II, the Serbian Prince Mihailo Obrenovic, and Serbia's political giant, Ilija Garashanin.

Ruling over the barely literate warriors in the mountains (the aerie of the eagles) was the Miltonian poet, romanticist, and classicist, Petar Petrovic-Njegos II, the spiritual and secular leader of Montenegro.This tall and handsome man had been instructed: "Pray to God and stick with the Russians," the political credo he heard at the deathbed of his predecessor. Njegos must have wondered at that advice. He must have recalled that as a young man he visited Russia and was well-received by Catherine II, but not so well by the mighty Prince Potemkin, who threw him out of the country (Serbian historian Stanoje Stanovjevic says that Njegos "swore never again to set foot on Russian soil").

Njegos had no love for his Muslimized Slav brothers and approved of the Christmas Eve massacre of the converted Montenegrins mentioned previously. He once wrote to the vizier of Skadar, who was of Slav blood: "When you talk to me as a Bosnian, I am your brother, your friend. But when you talk to me as a stranger, as an Asian, as an enemy of our tribe and our name, to me this is adverse." Njegos knew that the only lasting thing in this cosmos is change. He knew that, once large powers such as Austria and Turkey were toppled, there would be room for the development of a South Slav brotherhood. He spent a good deal of time in the doge's library in Venice and had "five or six secretaries transcribing for three weeks everything in the archives that had anything to do with South Slavism." At Cetinje (1845) the English visitor Sir Gardner Wilkinson had difficulty in fathoming Njegos, whose hobby was shooting lemons thrown in the air and who could elaborate on philosophy and transcendental themes while gazing at the heads of decapitated Turks on the wall in Cetinje. The visitor from London was horrified!

When asked what he would do if his dream was realized in his lifetime, the bishop said wistfully: "In that case I would go to my patriarchate in Pec and Serbian Prince Mihailo to Prizren" (the priest to the see of the Serbian spiritual leader, the secular ruler to the city of Dusan).

Serbia's Prince Mihailo Obrenovic (Milos' son), educated abroad and of poetic inclination, was just as much of a romantic, a dreamer, and a

compulsive visionary as Njegos. Slobodan Jovanovic says: "Mihailo's plans were not devoid of fantasies, they were too ambitious and sky-reaching ... His belief in the heroism of the Serbian people, his confidence in 1 general Balkan uprising, his persuasion that the Turkish Empire can be destroyed in one blow - all this is pure political romanticism ... Never have Serbs been so proud, and never have they believed so strongly in their own historic mission." (Druga vlada Milosa i Mihaila [Second reign of ... ] Belgrade, 1923, p. 263).

Mihailo's rule was short-lived, but inspirational, He ignited the nationalist flame that spread far beyond the borders of that day's Serbia. It was an all-Slav flame, shared by South Slav young intellectuals and even by a Roman Catholic bishop in Djakavo (Croatia), Juraj Strossmayer, who founded the Yugoslav Academy in Zagreb (1867). The bishop and the prince carried on an extensive correspondence on the formation of a "Yugoslav state," and the Slav visitors in Belgrade coffeehouses were fraternizing with Serbian youths, verbalizing about the "Balkan federation."

How did Albanians fit into this prevailing mood of Montenegro and Serbia? Not very well, if at all. When one consults the political realist of the first order, Ilija Garashanin, Mihailo's foreign minister, Albanians were a big "nuisance." Garashanin's name indicated that he was a village man (garashi), but his thinking was as international as Talleyrand's or Metternich's. He knew that ultimately only "united South Slavs" could prevent foreigners (Austria and Russia) from moving into the vacuum created by the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. He knew the importance of having Greeks and Albanians on the side of the Slavs. He had no illusions about Russian politics in the Balkans, but he could see where Russian and Serbian political interests could coincide.

Garashanin knew that Austria thought otherwise. In 1853 he wrote to his friend, Serbian diplomat Marinovic: "Austria will never support the progress of Serbia ... It would be stupid to think any other way." He was positive of Austria's inimical attitude, for the simple reason that it had such a large Slav population within its own borders. Scared of provocation, Austria would watch out for anything that could stir the Slavs. Garashanin advised Mihailo to do everything possible to win the Albanians over to the Serbian side, or at least to neutralize them - not to view them as Turks, but to "endeavor to persuade them to secede from the Turks." This would be no easy task, said Garashanin, because they were dealing with people who could neither read nor write and who were prone to suspicion. Garashanin was fully aware of secret accommodations made by Russia and Austria with Turkey - the whole game of "spheres of interest" and the negative role the Albanians were assigned in that game. This is why Belgrade diplomacy and Serbian money in the 1860s were very active among Albanian leaders, especially the Roman Catholics

of northern Albania, to lure them away from Italian and Austrian influence. In 1 year 5 separate Albanian tribal leaders were Garashanin's guests in Belgrade .

Had Garashanin been successful, had he indeed talked the Albanians into rebelling, would the estrangement process have been turned around? It is probable that this would have occurred in such circumstances. Had Prince Mihailo's life dream not been brutally interrupted by an assassin's bullet in 1868, the Balkan "powder-keg" would probably have exploded long before Albanian atrocities had gone too far to be disregarded. But mistrust between the 2 peoples deepened, and anti-Serbian policies of the foreign powers were too deeply entrenched for little Serbia to handle alone. Who knows, had the "keg" exploded some years before Austria went into Bosnia, Herzegovina, and the Sandzak, perhaps Bishop Njegos and Prince Mihailo would have ended up in Pec and Prizren respectively. And Serbs and Albanians might have had a better chance of being friendly neighbors.

|