Kosovo

by William Dorich

Kosovo

by William Dorich

|

|

Alex Dragnich and Slavko Todorovich

World War I and New Tutelage for Albania

As the end of World War I approached, and Serbia inched ever nearer to the fulfillment of its war aim - the unification of all South Slavs in one independent state - relations with Albanians took a new turn. The mighty Albanian protector, and the main instigator of anti-Serbian attitudes in the area, Austria-Hungary, was about to leave the historical scene. That was the good news. The bad news was that it was about to be replaced by Italy, which during the war had settled Albanians in Serbian areas, certainly not a friendly act. Moreover, Italy had the support of the West, which Vienna did not. The Entente had made numerous promises to Italy in the Secret Treaty of London (1915), and Italy wasted no time in seeking to achieve its objectives.

As the end of World War I approached, and Serbia inched ever nearer to the fulfillment of its war aim - the unification of all South Slavs in one independent state - relations with Albanians took a new turn. The mighty Albanian protector, and the main instigator of anti-Serbian attitudes in the area, Austria-Hungary, was about to leave the historical scene. That was the good news. The bad news was that it was about to be replaced by Italy, which during the war had settled Albanians in Serbian areas, certainly not a friendly act. Moreover, Italy had the support of the West, which Vienna did not. The Entente had made numerous promises to Italy in the Secret Treaty of London (1915), and Italy wasted no time in seeking to achieve its objectives.

But Italian and Serbian (Yugoslav) claims to former Austro-Hungarian territories overlapped. Serbia wanted Skadar, as a natural part of Montenegro, the real hinterland of the city. In vain, Montenegrins had spilled so much blood for it in the recent past. The new government in Belgrade wanted a degree of influence in Albania, especially in the northern part, and a few frontier "corrections." In general, Belgrade could live with the borderline drawn by the 1913 London Conference. Also, as it turned out, Yugoslavia was among the few voices among the allies, pleading for an independent Albania, free of any Great Power patronage.

The Serbian (Yugoslav) position was markedly different from the Italian. The disparity was not only with respect to territorial demands and ambitions, but mainly in the conceptual aspect of the demands. Italy, which had begun with an interest in the Albanian littoral, now wanted half of Albania and was pushing the Great Albania concept, which meant the incorporation of Serbian lands, such as Kosovo, into the new Albanian state. There was no way that such a proposal would be acceptable to a nation that had just come out of the war a winner.

Belgrade's position on Kosovo was not negotiable and had not changed one iota since the discussions at the London Conference of Ambassadors (January 1913). Serbia could not allow the Kosovo area to be a "malignant tumor" that would affect Serbia's state power. And, Serbia never considered Kosovo as "small change" or a "bargaining chip" to be used by diplomats at the negotiating table. Finally, the Serbs could have used the right of conquest argument, since the Turks had conquered it from them, but chose not to do so. Rather, they stressed Serbia's historic, cultural, and moral rights.

The historic, cultural, and moral reasons which guided Belgrade in opposing foreign pretensions to Kosovo were fully presented to the London meeting in 1913, and did not change in 1919 in the Royal Yugoslav format, and are just as valid today, some 70 years later, although in a diametrically different ideological context. The memorandum submitted by Serbia's delegates to the 1913 conference, read in part:

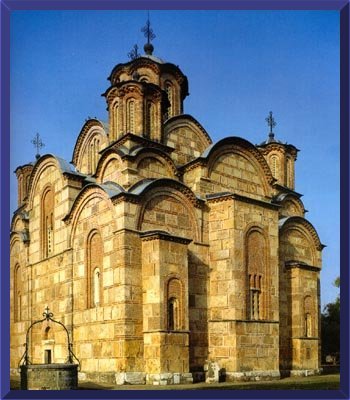

"Today the majority in those areas are Arnauts [Albanians], but from the middle of the 14th century until the end of the 17th century that land was so pure Serbian ... that the Serbs established their Patriarchate in Pec ... and near Pec is the Serbian monastery, Decani, the most famous monument of Serbian architecture and piety from the 14th century. It is impossible to imagine that [these] would have been built in a region in which the Serbian people was not in a majority. The region in which are found Pec, Djakovica, and Decani, is the most holy among all Serbian lands. It is impossible to imagine any Montenegrin or Serbian government which would be in a position to yield that land to Arnauts or to any- one else ... On that question the Serbian people cannot and will not yield, nor enter into any agreements or compromises, and therefore the Serbian government is not in a position to do so ... "

One cannot overemphasize the moral impact that the liberation of Kosovo (cradle of the nation) had as a fulfillment of Serbia's historic mission. Rational Western diplomats had difficulty understanding this. Operating in societies where traditional values are, if necessary, also negotiable, they viewed Serbia's history in terms of "progress" made in a brief span of time. They could not understand the uncompromising position of the Serbs when it came to losing a few cities here and there compared to the overall national advantage gained in only a few years. The "some you lose, some you win" philosophy could not be applied to Kosovo. Serbia just could not accept the Entente's concept of giving certain Serbian lands to Serbia in exchange for giving other equally historic Serbian lands to someone else.

European diplomatic big guns like Lloyd George (who in 1919 said, "I've got to polish off Pashic") or Izvolski (who once called Pashic, "this old conspirator"), as well as British public opinion molders such as Wickham Steed and R. W. Seton-Watson, were plainly annoyed with Serbia's stubbornness. The latter twosome envisioned the new state of the South Slavs in terms of a Central Europe constellation. They feared Serbian "hegemonism" and fell for Italian scare tactics, portraying the Slav monster as "stretching from Vladivostok to the Adriatic." To them, the fact that Tsar Dusan (1331-1354) had 1 of his palaces adjacent to Skadar, that that city was the capital of the Montenegrin ruling family of Crnojevic (1465-1490), that the widow of Serbia's King Uros (1242-1276) built her monastery there and lived there as a nun, that Skadar had a Serbian school as late as 1850, and that the city was ecclesiastically part of the Prizren Orthodox diocese until 1913 - all this meant nothing, or very little.

Once again, the Serbs had an image problem in Western Europe. Again, the British Foreign Office had suspicions regarding Serbian motives. Serbian historian Milorad Ekmecic writes: "The Serbian Government could not get rid of the burden which history has placed upon her shoulders - the prejudice in Western Europe about the historic mission of Serbia, which is to open the door to the Russians in the south of Europe ... Britain viewed Serbia exclusively from that perspective." (Ratni ciljevi Srbije 1914 [War Aims of Serbia], Belgrade, 1973, p. 437).

The Albanian authors, Stefanaq Pollo and Arben Puto (The History of Albania, London, 1981, p. 182), assert that there were other considerations. In explaining the admission of Albania to the League of Nations in 1920, they write:

"The unexpected interest in the Albanian cause on the part of London was not unconnected with the petroleum wealth to be found in the Albanian subsoil .... The Foreign Office told the Tirane Government that it could count on Britain's firm support if it allowed the Anglo-Persian Company exclusive rights to prospect and exploit the petroleum resources in Albania. The Government accepted [the offer] and so, on December 17, the British representative, H. A. L. Fisher, declared to the General Assembly that his delegation had undertaken 'a new and thorough study of the Albanian situation' which has convinced it that Albania should be admitted immediately. "

The validity of this contention is beyond the scope of this study, but suffice it to say that Britain did on different occasions support Albanian positions against Belgrade. Moreover in 1921, Britain was influential in the Conference of Ambassadors (this time in Paris), which, in addition to deciding on the borders of the new state, resolved that the territorial integrity of the Albanian state to be a matter of "international interest." Consequently, it was agreed that Italy was to be endowed with the "protection" of Albania within the League of Nations system. This meant giving Italy a hand in Albanian internal affairs, which seemed to put Belgrade on notice of Italian intentions in the Balkans.

Serbian Premier Nikola Pashic had something to say about United States attitudes toward Serbia in those days. He had nothing against Wilson's 14 points or his steadfast defense of the right of self-determination. But he felt that there was a flaw in Wilson's personal insistence on Albania's "independent" status. In the view of the seasoned Serbian politician, an "independent Albania" under an Italian "protectorate" was a contradiction in terms. Pashic believed that it would have been more logical to have the 2 states, Serbia (Yugoslavia) and Albania, cooperate in defending the Balkan area against intrusions of foreign influences of all kinds. In one report to the National Assembly Pashic declared that on the one hand Wilson "protects Albania from us, and on the other hand, he brings Italy into Albania, the most dangerous enemy not only of the Albanian people, but of the whole Balkan peninsula as well."

In this "exit Austria - enter Italy" scenario Pashic saw the opposite of freedom from foreign intervention in Balkan affairs. In the multinational environment of the Balkans ethnic tensions and national conflicts were not to be dreaded as much - he thought - as the exploitation of those tensions and rivalries by a foreign power. Even if one attempted to understand the concern of the Entente (and the United States) about maintenance of peace in the Balkans, to appoint Italy to be the protector of Albania and, indirectly, the guardian of the peace in the area was equal to assigning a fox as caretaker of the chicken coop, as events in the 1930s were to demonstrate.

|