Kosovo

by William Dorich

Kosovo

by William Dorich

|

|

Alex Dragnich and Slavko Todorovich

The Saga of Kosovo

Prefatory Comments for the reader:

References in the text have been kept to a minimum, but a selected bibliography and annotated index have been appended as an aid to pronunciation. Instead of using diacritical marks over certain letters, added letters are provided so as to approach the correct phonetic

sound. The only exceptions: when to do so would change the beginning letter of a name or place, and where a name is a direct part of the cited work. Inclusive dates after the name of early Serbian rulers, or other high officials, indicate the years of rule. Dates after place names, notably historic monuments, indicate the approximate years of their construction.

Serbia and Montenegro and Serbs and Montenegrins are both frequently mentioned in the text, but it should be kept in mind that Montenegrins are Serbs and in their earliest history Serbs and Montenegrins were one nation. As historical developments took their course, however, two Serbian states (Serbia and Montenegro) evolved and were again united only in 1918. It is therefore more convenient and probably less confusing to adhere to the historical designations. Moreover, post-World War II Yugoslav rulers created Montenegro as one of 6 Yugoslav republics, and in population statistics they have insisted on Montenegrin as a distinct and separate national group. In the discussion of Yugoslav Albanians occasionally the word Schipetars (Shiptari in Serbo-Croatian) has been employed, a term which has been in popular usage among Yugoslav citizens.

Introduction

In March and April 1981, large-scale disturbances broke out in Yugoslavia's autonomous Province of Kosovo, which is part of the Republic of Serbia but populated mainly by people who look upon themselves as Albanians. The riots were spearheaded by students from the province's university in the city of Pristina. The disorders originated in the cafeteria, allegedly as a demonstration protesting the poor quality of the food served to the students. Within a few days demonstrations not only occurred in other parts of Pristina, but in several other Kosovo cities as well. More important, however, was the fact that they took place on a political cast, with slogans that suggested disaffection with Yugoslavia and a desire to unite with Albania. The riots were put down with an indeterminate loss of life.

In March and April 1981, large-scale disturbances broke out in Yugoslavia's autonomous Province of Kosovo, which is part of the Republic of Serbia but populated mainly by people who look upon themselves as Albanians. The riots were spearheaded by students from the province's university in the city of Pristina. The disorders originated in the cafeteria, allegedly as a demonstration protesting the poor quality of the food served to the students. Within a few days demonstrations not only occurred in other parts of Pristina, but in several other Kosovo cities as well. More important, however, was the fact that they took place on a political cast, with slogans that suggested disaffection with Yugoslavia and a desire to unite with Albania. The riots were put down with an indeterminate loss of life.

Although the problem of Kosovo is complex and complicated, for about one-half of Yugoslavia's population, the Serbs, it is not. To them Kosovo is holy ground. It is the cradle of their nationhood, when they were virtually its sole occupants. It was the center of Serbia's empire of the Middle Ages, at one time the strongest empire in the Balkans. It was in Kosovo in 1389 that Ottoman forces won the crucial battle with the Serbs, leading to the end of their empire. But Kosovo is also the place where Serbia's most historic and religious monuments are located.

To understand today's Kosovo and its problems, as well as how it relates to Yugoslavia's relations with Albania, and even to the possibility of foreign intervention under certain conditions, it is necessary to know what happened in the area during the intervening centuries of Turkish rule, when the Serbs could do little more than seek to preserve Kosovo as a symbol of their identity, their greatness, and the hope of their ultimate resurrection.

Our story begins at the time when the Church of Constantinople and the Church of Rome were unable to find common ground. The Eastern Empire (Byzantium) lost Asia Minor to the Turks (1071) of the Seljuk tribe. This meant an equally disastrous blow to the Western world, because it affected the profitable trade routes to the markets of the Far East. Venice, Pisa, and Genoa had an extensive commercial interest in those routes. Under the excuse of the "saving of Christ's burial place," Western crusaders found their way to Byzantine treasures, looting Constantinople in 1204, and breaking up Byzantium into three states: Epirus, Trebizond, and Nicaea. This is when Serbia emerged as an independent state, subsequently an empire.

In 1261, Byzantine leader Michael Palaeologus finally succeeded in recapturing Constantinople, but the restored empire lacked its former strength. With the old foes (Latins) still around, plus the rise of the Slavs (Serbs and Bulgars), the Byzantines turned to the Turks for help, only to see the Turks at the walls of Constantinople (1359), their victory over the Serbs at Kosovo (1389), and their taking of Constantinople (1453).

For our purposes, it is necessary to have some picture of what happened under the rule of the Ottoman Turks, who subsequently were to reach the gates of Vienna. It is also useful to have some picture of how Serbia managed its resurrection in the 19th century, and how it liberated Kosovo in the Balkan wars (1912). And it is also essential to have some appreciation of the impact of World War I and later attempts to deal with the question of Kosovo.

In addition, it is imperative to understand how World War II affected Kosovo, and how the Yugoslav Marxists proposed to deal with the problem of nationalities, and how they "solved" the Kosovo question.

Finally, we shall look at the nature of Yugoslav Communist rule in Kosovo and some of its consequences. At that point we shall raise some questions about the future, speculate about Kosovo's destiny, and examine the possible impact of what happens in Kosovo upon international relations, including those of the Great Powers.

KOSOVO AND MEDIEVAL SERBIA

Kosovo is many diverse things to different living Serbs, but they all have it in their blood. They are born with it. The variety of meanings is easily explained by the symbolism and emotions that the word "Kosovo" embodies, clearly above anything that the geographic concept might imply. It is in Serbian blood because it is a transcendental phenomenon.

Serbs who have a visual memory of the Kosovo region see it as a somewhat sleepy valley with surrounding hills seeming to have overstretched in their descent. Some 4,200 square miles in size (with an additional 2,000 square miles of adjacent Metohija), this cradle of the Serbian nation is carried by 2 broad-shouldered gentle giants, somber and dark Mount Kopaonik in the north and white-capped and fair Mount Shara in the south.

Kosovo, comparatively, is good pastureland, as well as corn, wheat, and fruit land. Yet Kosovo peasants can barely scratch out a subsistence tilling the clayish soil that is exposed to winds that dry the ground. For these peasants, Kosovo provides a lean and meager lot.

To others, Kosovo is a breadbasket. To those who descended from the slopes of the mountains, or who came there from poorer regions as homesteaders, Kosovo seems a promised land. Kosovo is a bottomless ancient mining pit, rich in zinc, lead, and silver, but it is not a melting pot.

Kosovo is a plain where the Serbs bend over to work the soil, Albanians sweat in the mining shafts underground, Turks (largely spent and reminiscing about past glories) grow poppies and peppers, while the Gypsies fill the air with the sounds of life. To the Serbs, that plain of suffering, of want, and of sacrifice is holy ground. They come there to clench their fists and shout at the earth where dead Turks lie. As Rebecca West has written, "Dead Christians are in Heaven, or ghosts, not scattered lifeless bones ... only Turks perish thus utterly."

The Lord Almighty, some might say, must have predestined Kosovo as a battlefield, a rendezvous for hostile earthly encounters. It is a junction that led many a nation astray, if not to a dead end. Byzantines, Bulgars, Serbs, Magyars, Austrians, Albanians, and Turks - all marched

through it at certain times, but in a sense got nowhere. Kosovo can be viewed as nature's boxing ring where world ideologies (Christian, Bogomil, Muslim, and more recently Marxist) each won individual rounds, but not the fight. There must have been 6 major human slaughters in as many centuries on this peaceful stretch of land. The soil in this valley appears to have fed on human flesh and blood.

Kosovo is commemorated in that heartbreaking medieval em-broidery made in 1402 in the stillness of the Serbian Monastery of Ljubostinja with the needle of the pious Serbian Princess Euphemia. She sketched her requiem in gold thread on a pall to cover the severed head of Prince

Lazar: "In courage and piety did you go out to do battle against the snake Murad ... your heart could not bear to see the hosts of Ismail rule Christian lands. You were determined that if you failed you would leave this crumbling fortress of earthly power and, red in your own blood, be one with the hosts of the heavenly King ..."

Kosovo is a grave, and a grave means death and dust. But it also means rebirth and a source of new life. Kosovo is therefore transcendental.

Serbia as a nation came into its own sometime in the 11th century, in the center of the Balkan peninsula, which at that time was within the vast realm of the mighty Byzantine Empire. A lighthouse between 2 continents, Constantinople in those days was a beacon light for all sorts of wayfarers: those in submission, those in power, those in revolt, those hungry for culture, and those driven by greed. As any potentate, Constantinople at that time had no friends in the whole world.

Byzantium had very little reason to cherish the Slavs in the Balkan area, Serbs or Bulgars, because they proved to be a lasting nuisance from the time of their arrival, together with or before the marauding Avars. To Byzantium, incursions of most barbarians were basically a passing irritant, for even when they ransacked the walled cities they soon left. Slavs, on the other hand, inherently were not nomadic types. Once having arrived, they tended to settle, and by doing so they changed the ethnic character of the area.

Byzantine rulers, especially Emperor Basil II, tried to drive the Slavs out, particularly the Bulgars, but in the long run military valor gave way to political realism, which forced the beleaguered Byzantine emperors to accept Serbs and Bulgars as permanent inhabitants of the Balkan peninsula. In time they learned to deal with the Slavs on almost equal terms, partly because there were more serious problems confronting them. There were the Persians, Muslim Arabs, and Seljuk Turks, who kept the Byzantines occupied in the east for several centuries. In the west the Normans and the Venetians were sapping Byzantium's military strength. The Slavs, for their part, exploited these troubles to expand and solidify their positions. Even after Constantinople managed to restore much of its imperial prestige, it was challenged in the north by the invading Magyars, who waged 4 successive wars against Byzantium.

This presented the Serbian ruler of Raska (Nemanja, 1168-1196) an opportunity not to be missed. He moved quickly toward Serbian recognition and independence. It was not an easy task, and he was not continually successful in the process. There was a time when his supporters, Hungary and Venice, could not help him. Facing the angry Byzantine Emperor Manuel I alone, Nemanja was defeated and taken a prisoner to Constantinople, where he was led through the streets with a rope around his neck, to the wild rejoicing of the crowds. It must be remembered that protocol and symbolism meant a great deal in Byzantine culture, so that when Nemanja was brought to submission he had to present himself barefooted and bareheaded, offering his sword and prostrating himself on the ground.

Since Raska was under the overlordship of Byzantium, Manuel thought that his humiliation of an unfaithful prince would be enough and let Nemanja return to his people. In addition, Nemanja was forced to pay tribute and to provide auxiliary (support) troops. What really may have saved Nemanja's life was the proximity of Raska (which by that time had already merged with Zeta, another Serbian principality) to the Western world. After all, at that time Christendom was seriously endangered by Islam, and the emperor badly needed the support of the West, and even of those annoying Slavs in the Balkans.

When Westerners marched toward Jerusalem the natural route was through the Morava Valley, which was inhabited by the Slavs. In fact, when one of the leaders of the Third Crusade (Barbarossa) came through that area in 1189, Nemanja met him at the border of Raska and proposed that he forget about Jerusalem and instead occupy Constantinople, but at that moment Barbarossa was not interested.

Byzantine rulers, for their part, did not know whom to trust. And, in the confused evolution of developments, Nemanja sought to exploit the situation. He played the Latin world against the Greek, and in the process obtained from the West political recognition for Raska and a crown for his son Stefan. A papal delegate delivered the crown in 1217. Soon thereafter Stefan the First Crowned turned to the East, obtaining ecclesiastical independence for Raska from the patriarch of Nicaea. This was in fact the work of his brother Rastko (Monk Sava), who was ordained the first native Serbian archbishop. All Serbs know that Sava began the illustrious line of Serbian archbishops and patriarchs who led the Serbian Church and people through the ensuing dark times, when the Muslim curtain had fallen upon the Balkans.

Raska (now the Kingdom of Serbia) continued its rise. After spreading its wings, Raska never ceased being the nucleus of the nation. The small river that supposedly gave Raska its name is part of the Ibar River Basin, located a few miles north of Kosovo. The capital of Raska was the city of Ras, which was in the vicinity of today's Novi Pazar. The precise location of Ras has not been positively established. Some believe it to be at the location of Eski (Old) Pazar, but no ruins were found. The historian Jirecek, who is considered the outstanding authority on medieval Balkan affairs, maintains that Ras was the same place as the one called "Trgoviste," an important commercial center and caravan station used by Dubrovnik merchants until 1445, when the Turks built Novi Pazar.

Another important Serbian town was Dezevo, which derives its name from the rivulet Dezevka (left tributary of the river Raska). It was built around the royal court to replace the antiquated facility at Ras. This is the place where in 1282 King Stefan Dragutin, ruler of the northern regions of Serbia and Srem, abdicated in favor of his brother, King Stefan Milutin (1282-1321), who until then had ruled the southwestern parts of Serbia. In the immediate vicinity of Ras and Dezevo are the well-known old Serbian Monasteries of Sopocani and Djurdjevi Stupovi.

Serbian medieval documents use the terms "Rascian lands" and "Rascian king" only in a few instances. Serbs nearly always referred to their territories as Serbian lands, especially in the post-Nemanja period. Merchants and diplomats from the coast city Republic of Dubrovnik, who maintained close links with Serbian authorities and courts, used Vatican nomenclature and called Serbia "Slavonia," although subsequently they adopted the term "Serbia."

Because the 2 main caravan routes to Constantinople passed through Serbian territories, custom bills were due to Serbian rulers, complaints were filed, requests for protection or bailing out of jail submitted, down payments made, and court cases litigated. Thanks to all the resulting documents, filed in the Dubrovnik archives, historians have been able to reconstruct the fabric of life in medieval Serbia.

Serbian rulers, in a manner of speaking, were seeking to pursue a "non-aligned" policy. On the one hand they fought Byzantium, but could never rid themselves of its spell. Serbia was never governed directly by Byzantium'but, as the well-known Byzantinist, George Ostrogorski, says: "... It is impossible to separate its medieval history from Byzantium." Constantinople was the cultural capital of the world at that time. No wonder that young, emerging, neighboring states should look to it as a model. At times the Serbs were successful in their struggle against Byzantium. Tsar Dusan (1331-1355), whose formative years were spent in Constantinople during his father's exile there, conquered half of it (Macedonia, Epirus, and Thessaly), and made Serbia the strongest empire in the Balkans. Serbia's territory in Dusan's time covered the vast area from the Danube to the lower Adriatic and the Aegean. He signed his edicts: "Emperor and Autocrat of the Serbs, Byzantines, Bulgars, and Albanians."

Dusan did not hide his ambitions to aspire to the throne of Byzantium. In 1345, he conquered Serres, an important city in Greece on the road to Constantinople. He wanted the powerful Greek clergy in Byzantium to recognize him. When the patriarch at Constantinople hesitated to crown him, he summoned the Serbian and Bulgarian bishops for a council at Skoplje. The bishops raised the autocephalous Serbian archbishopric of Pec to the rank of patriarchate (1346), and in less than a month the newly elected Serbian Patriarch Joanikije II crowned Stefan Dusan emperor.

Dusan may have grown up in Constantinople, but he also sought approval in the West, notably from Venice and the papacy, suggesting that he be regarded as "Captain of Christendom." To be sure, Dusan had subjugated the center of Byzantine Christianity, Mount Athos. This oasis of poverty, chastity, and obedience (the three vows that every monk was required to take) was a beacon that attracted souls yearning for peace and education. Secular Balkan leaders at times found this place a reservoir of skillful hands and brilliant minds from which they recruited.

Dusan traveled to visit the Serbian monastery (Hilandar) on Mount Athos, together with his wife Jelena, a feat in itself, because no female (human or animal) was ever permitted to set foot on the peninsula of Mount Athos. Today, as one visits Hilandar and walks the path leading from the small harbor to the monastery, there is encountered a stone cross-like monument where allegedly Empress Jelena heard the voice of the Blessed Mother, warning her not to enter the monastery but to stay at the spot where she was. Even the monks who tell you this story today

shake their heads in reverent awe and say: "I wonder who would have dared say that to Dusan the Mighty!"

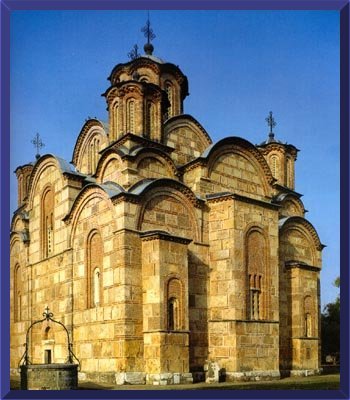

The influence of the Romanized world, on the other hand, was far from negligible, and at times a source of great tension. In the entourage of Serbian kings, Roman Catholic courtiers, German guards, and foreign ladies wed to Serbian kings tried to interject aspects of Latin style, fashion, and mores. The best Serbian application of Romanized culture is Stefan Decanski's (1321-1331) beautiful Monastery Church of Decani, built by a Franciscan friar and Dalmatian stone masons, with fresco works by artists of the Kotor school . It is known, however, that both King Milutin and later Stefan Decanski's son, Tsar Dusan, were occasionally annoyed by the Western influence but tolerated it.

Most of Dusan's imperial time was spent in the Hellenic area of his realm. Knowing Greek, he felt quite at home there, leaving central Serbia in the care of his son Uros. Dusan replaced the Greek aristocracy with Serbian administrators, his comrades in arms, and gave them Byzantine titles. This could not have pleased the inhabitants, but Dusan was more interested in courting Venetians, who could give him the ships necessary to take Constantinople. But to the Roman Catholic West, Dusan was and remained an "Eastern schismatic" who was not to be trusted. In a sense they were right, because Dusan was seeking to shape the culture of his realm through the use of the Serbian clergy and nobility, recruited from the Serbian peasantry, anti-Western as much as anti-Eastern.

*** Serbia of the Nemanjic dynasty was without doubt a land of economic and cultural progress that surpassed the existing European average. Apart from the well-known monasteries and their impressive frescoes, there are smaller but masterly art objects from that era: golden cups and chalices, candlesticks and silver plates, jeweled reliquaries, delicate embroideries, book bindings, and artistic illuminations - produced by talented people in a society which gave them an opportunity to express themselves. As for the Serbian rulers, unlike those in the West, they did not build enduring castles, but each one of them felt duty-bound to build at least one monastery.

In the legal-governmental sphere, Tsar Dusan's Code of Laws (Zakonik), studiously prepared over a period of about 6 years (1349-1354), is recognized by legal scholars to be among the leading law systems of the world.

Moreover, medieval Serbia was also a part of the international community, relating on a state to state basis in matters of political, military, and cultural concern. Serbian royal courts communicated on levels of respect and honor in diplomatic relations with Venetian doges, Hungarian kings, Bulgarian tsars, and Byzantine emperors. In addition, they were connected through marital arrangements with most of them. The first wife of Stefan the First Crowned was Eudocia, daughter of Byzantine Emperor Alexis III. King Stefan Uros I married the French princess Helene (House of Anjou), and Stefan Dragutin married Katherine, daughter of Hungarian King Stephen V, just to name a few.

It is only natural that a society with its own alphabet, language, state, and autocephalous Church should have the urge to create its own literature and culture. A large body of Western medieval literature, such as the Old and New Testaments, liturgical books, theological treatises, dogmatic and apocryphal works, and chronicles and life stories of the saints, was present either in the original or in translation. And major medieval novels, such as tales about Alexander the Great and Tristan and Isolde, were also known. But this was not enough. The need to have their own literature was strongly felt by Serbian rulers and their associates.

Among the Serbian medieval literati were ecclesiastics and laypeople. Two of them were of royal blood, although not technically because Nemanja was not crowned (Nemanja's two sons, Stefan and Rastko-Sava - a rare case in the world's history), and one was of noble princely heritage (Prince Lazar's son, Despot Stefan). Others were of peasant stock, educated as monks or priests. Still others were foreign-born and highly educated, having found cultural refuge in Serbian courts or monasteries. The very proximity to the great Hellenic culture almost guaranteed that many cultured men would be roaming the Balkan spaces.

Monastics, courtiers, and a maze of Slavic-speaking subjects of Venice, Byzantium, Hungary, and Bulgaria swarmed around Serbian literary centers. Knowing the Serbian language was an asset in other than literary activities. Venice and Byzantium, and later the Turks, quickly discovered that interstate and other correspondence was likely to be more efficient if carried out in Serbian.

One of those yearning for peace and education was the Serbian Prince Rastko (Sava), Nemanja's youngest son, mentioned above. Clandestinely, he left the court. One stormy night he banged on the heavy wooden gates of a Mount Athos monastery (Panteleimon), pleading with the monks to let him in and save him from the inclement weather and a posse. He was admitted and began to study theology, languages, and history. His aging father subsequently joined him and purchased an old ruin where the building of the Serbian Monastery of Hilandar was begun a short time before he fell ill and died.

The respectful son later wrote a biography of his beloved father, the founder of the dynasty and Serbian statehood.

He titled it The Life of Master Simeon, a work dealing not with the secular Nemanja but with the spiritual Simeon, the monk of noble heritage. In addition to a profusion of translated church manuals, canonic and instructive texts for use by Serbian monks and priests back home, Sava also tried his hand at verse writing. Being the most traveled Serb of his time, Sava visited and personally knew several Byzantine emperors (Alexis III Angelus, Theodore I Lascaris, and John III Vatatzes), and the patriarchs of Constantinople (Athanasius) and of Nicaea (Manuel). Sava knew the frailty of men, the mighty and the weak.

In a poem, entitled "Word about Torment," he writes:

"Dead am I even before my death,

I sentence myself even before the judge does,

Even before the ceaseless pain sets in.

I am already tortured by my own agony."

Sava's brother, King Stefan the First Crowned (1196-1228), also wrote a biography of his father. But being occupied with matters of state, he had little time for spiritual preoccupation, and hence his biography is written from the point of view of a dynast, national ruler, protector of the faith, and statesman. While Sava had been of invaluable help to his brother in consulting about national affairs, he did not write about such matters. Stefan began writing the biography after Nemanja's body had been brought to Serbia (Studenica Monastery) in 1208 and finished it in 1216. Other Serbian writers later wrote about Nemanja, but none with such a wealth of detail and so informatively.

Subsequently, a new generation of Serbian authors wrote about Sava and King Stefan, particularly the monks Domentijan and Teodosije (second half of the 13th century), both of the Hilandar school. There were authors who attained high ecclesiastical posts, such as Archbishop Danilo II (1324-1338), who personally knew 3 Serbian kings (Dragutin, Milutin, and Stefan Decanski). He wrote a historical essay on the "Lives of Serbian Kings and Bishops." His poem, "The Lament of Bulgarian Soldiers for Tsar Mihail," is a part of every Serbian anthology (Mihail was Stefan's father-in-law, killed in the Battle of Velbuzhd, 1330, the battle that ended Bulgarian primacy among Slavs in the Byzantine sphere. Among Serbian medieval patriarchs, the best of the literati was Danilo III (elected at the Council of Zica, 1390), who, together with Lazar's widow Milica and her children, transported the body of the beheaded prince from Pristina to the Ravanica Monastery and canonized Lazar.

As for Lazar's son, Despot Stefan (1389-1427), he was an exceptional person indeed. A dashing man of war, letters, and politics, he was the hero of the Battle of Angora (Asia Minor, 1402), where he fought as a Turkish vassal for Bayazet, the killer of his father. Of the 3 Serbian vassals in Turkish ranks at the earlier Battle of Rovine (in Walachia in 1395 against Prince Mircea), Stefan was the only one who survived. The popular King Marko of Prilep and Konstantine Dejanovic of eastern Macedonia perished. Despot Stefan was a great benefactor, protector of refugees, writers, and artists. A humanist of wide culture, he was also an author in his own right. One of his poetic scripts is entitled: "Love Surpasses Everything, and No Wonder Because God Is Love." Another was the "Ode to Prince Lazar," a beautiful text chiseled in the marble column which was placed at the spot of the Kosovo Battle. A third, "An Ode to Love," was dedicated to his brother Vuk, whom he once fought at that very Kosovo Field. In Stefan's monastery, Resava, generations of monks, scribes, and artists have worked unremittingly to preserve the Serbian heritage (the famous Morava school).

A great patriot and Serbian nationalist, Stefan Lazarevic had the misfortune of presiding over the declining days of his beloved country. Had he been Dusan's successor, instead of Lazar's, the history of the Serbian people might have been different. At a crucial time when Serbia had a chance to outdo Byzantium, Dusan's son Uros ruled (1355-1371). He was a weakling, lacking the necessary firmness and general leadership qualities. The respect and awe that Stefan commanded among the Turks and Tartars at Angora, when he rode at the head of 3 gallant charges against Tamerlane, in an effort to save his surrounded suzerain, speaks of the effect his presence might have had if he had inherited the throne in 1355, when Dusan died.

Today, with the benefit of hindsight, we can see the situation clearly, but could King Vukasin and Despot Uglesa ever have anticipated Kosovo? Could the Hungarian kings have foreseen Mohacs? Could John VI Cantacuzenus have known what he was doing to himself, to Byzantium, and to the Christian world, by leaning on the support of his powerful but dangerous Muslim ally? And the countries of the West, could they have known what their insistence on ecclesiastical submission to Rome, as a price of aid, would lead to?

When in desperation, Byzantine Emperor Manuel II begged for assistance from the pope, the doge, and the kings of France, England, and Aragon, his plea for help in fighting against the "infidels" went unanswered. The emperor spent several years on this tragic mission to Venice, Paris, London, and other cities. The trip was full of pageantry and had a certain cultural importance in terms of the early Renaissance development, but from a political point of view it meant only vague promises that remained unfulfilled. Reconciliation between East and West, the Greek and the Latin worlds, Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism, was a vexed question. The 2 sides did not attempt to do together what they were unable to achieve alone, i.e., to stop the Turks. One wonders, would there have been 2 sieges of Vienna (1529 and 1683) if Roman Catholic Europe had come to the aid of the Eastern Orthodox emperor (Dusan) in the 1350s?

Even the defeats at Nicopolis (a town in Bulgaria on the Danube, 1396), and Varna (1444), which wiped out all hopes for Christendom to clear the Balkans of Islam, could not bring unity. At Varna the Christian leaders did not have an opportunity to flee. King Vladislav of Hungary and Poland, and the pope's delegate, Cardinal Giulio Cesarini, fell on the field. Djuradj Brankovic, the last of the Serbian despots and a weak member of the Christian coalition, realized even before Varna that the coalition's chance for success was poor, and withdrew. This did not help, however, the despotate, which succumbed in 1459, 6 years after Constantinople fell to the Turks (1453). The black two-headed eagle of Byzantium moved to Moscow to become the symbol of the "Third Rome," nourishing the fancy of Balkan Slavs for centuries to come.

THE KOSOVO BATTLE

Of all Kosovo battles only one counts in the formation of the psyche of a Serb. It is the one that began in the early hours of Vidovdan (St. Vitus' Day, June 15, 1389) (June 28 by the New Calendar). The Turks had already been on the European continent for some time, seemingly unstoppable and intoxicated by easy victories over the rival and disunited "infidels."

The Battle of Kosovo took place on the part of Kosovo Plain that the Turks called Mazgit, where the rivulet Lab flows into the Sitnica River. Today's visitors learn where Sultan Murad's intestines were buried, where the Turkish standard bearer (Gazimestan) fell, where grateful Serbia erected a "memorial to the fallen heroes of Kosovo," and where a marble column once stood (placed there on the order of, and authored by, Prince Lazar's son, Despot Stefan Lazarevic), which had the following inscription:

"Oh man, stranger or hailing from this soil, when you enter this Serbian land, whoever you may be ... when you come to this field called Kosovo,

you will see all over it plenty of bones of the dead, and with them myself in stone nature, standing upright in the middle of the field, representing both the cross and the flag.

So as not to pass by and overlook me as something unworthy and hollow, approach me, I beg you, oh my dear, and study the words I bring to your attention, which will make you understand why I am standing here ...

At this place there once was a great autocrat, a world wonder and Serbian ruler by the name of Lazar, an unwavering tower of piety, a sea of reason and depth of wisdom ... who loved everything that Christ wanted ... He accepted the sacrificial wreath of struggle and heavenly glory ... The daring fighter was captured and the wrath of martyrdom he himself accepted ... the great Prince Lazar ...

Everything said here took place in 1389 ... the fifteenth day of June, Tuesday, at the sixth or seventh hour, I do not know exactly, God knows."

Following World War II, a redesigned monument was erected, a 25-meter tall tower, together with about 25 acres of the surrounding land, where the famous Kosovo peonies supposedly sprout from the blood of the Kosovo heroes.

The Serbian army in 1389 was encamped along the right bank of the Lab, an area suitable for both infantry and cavalry troops. The right wing of the Serbian army was under the command of Vojvoda Dimitrije Vojinovic. The left wing stood under the command of Vojvoda Vlatko Vukovic, sent by Bosnian King Tvrtko. Prince Lazar kept the command of the center for himself. The reserve was under the command of Prince Lazar's son-in-law, Vojvoda Vuk Brankovic. Prince Lazar had many reasons to worry about the outcome of the forthcoming encounter. Murad gave him no time to rally his vassals and tributary lords, some of whom were conspicuously slow in marshaling their troops. Lazar's frantic effort to obtain help from allies such as the king of Hungary failed because it was difficult, if not impossible, to organize it on such short notice. Nevertheless, although ill-prepared, Lazar had no other choice but to face the enemy. Murad's advisers, a group of extremely skilled military veterans, insisted on immediate and fast action. Amassed in the area of today's Nis and Kumanovo, the Turkish generals were eager to meet the Serbs while still possessing the momentum of previously victorious campaigns.

Morale in the Serbian camp was not high. Lazar's commanders were torn apart by local rivalries, ominous jealousies, and distrust. Djuradj Stracimirovic-Balsic, a prince of Zeta and son-in-law of Lazar, and some vojvodas of the northern regions were delayed by local "revolts" and opposition. Historians are still trying to ascertain whether the revolts were real or simply used as excuses. Two other of Lazar's sons-in-law, according to national tradition and accepted by some historians, were bitterly divided, under the influence of their wives. According to chroniclers, national bards, and traditional Kosovo saga, Vuk Brankovic of the old aristocracy, who married Mara, and Milos Obilic, of lesser birth, who married Vukosava, fell prey to the ongoing feud between the 2 sisters. (Lazar's genealogical history, as presented by the historian Aleksa Ivic, however, does not register Milos Obilic among Lazar's sons-in-law).

To make things worse, several well-known and gallant Serbian and Bulgarian princes were at that time already in the service of the Turkish conqueror, burdened by the obligations of vassalage. Among them, Dragas and Konstantine ruled in the area between Serres and Kustendil, while the sons of the late King Vukasin, Marko and Andrias, ruled as vassals in the regions of today's western Macedonia. One should keep in mind that at that time feudal mores required the vassal to serve his lord and not his people.

Prince Lazar could have taken some moral comfort from the fact that he and his people were defenders of Christian civilization and that the forthcoming battle would probably be the last chance for Balkan Christians to repulse the Muslims. Some historians will dispute the contention, but there are others who maintain that quite a few among the leaders in the neighboring states (from Bulgaria, the Danubian lands, and even from the area of today's Croatia) took part in the battle. It is indisputable, however, that among those who joined the Serbs were some Albanian princes. Even though no Albanian state had yet existed, Albanian tribes were close allies of the Serbs, and friendly relations between Serbian and Albanian chieftains were the natural result of their common desire to get rid of first the Byzantine and then the Turkish opponents. John Castriota (of Serbian origin), the father of the most prominent Albanian, Skanderbeg, came to Kosovo at the head of a combined Serbian-Albanian force mobilized in the area of Debar. Among auxiliary troops were the volunteers led by Palatine Nicolas Gara (Gorjanski), another one of Lazar's sons-in-law.

From the time that the Serbian notables and Church dignitaries met in the city of Skopia (Skoplje), after the fatal battle in which King Vukasin and his army perished (Marica, 1371), and chose Lazar Hrebeljanovic as their leader, he enjoyed great popularity and respect. In addition to his personal qualities, he was also the husband of Milica, the great granddaughter of Stefan Nemanja, the founder of the Nemanjic dynasty. He, therefore, had some hereditary right to the throne of Serbia. Wise, charitable, cultured, and a skillful soldier, he defeated the Turks in encounters that took place in 1381 and 1386, but it was becoming ever more evident that Lazar was winning battles but losing the war.

Lazar's Bosnian ally, Tvrtko I, defeated the Turks when they probed Bosnian territory (1386 and 1388). All this, however, made the Turks only more resolute, and as the year 1389 came, they were ready. The Eastern Christians in the Balkans were now faced not by scattered Turkish forces, but by a great army. Sultan Murad led his army straight toward Lazar's capital (Krusevac). There was a bloody Turkish assault on the fortress at Nis, which the Serbs defended heroically for 25 days. This is where Murad himself had an opportunity to evaluate the morale and effectiveness of the enemy. When Murad's scouts reported the concentration of a large Serbian army at Kosovo, he marched immediately to meet it. Thus, the Balkan Christians and the Muslims were locked in a decisive battle, a battle that the Muslims saw as an opportunity to break the backbone of Serbian resistance. According to Serbian bards and tradition, Murad sent the following message to Lazar:

"Oh Lazar, thou head of the Serbians:

There was not and never can be one land in the hands of two masters.

No more can two sultans rule here ...

Come straight to meet me at Kosovo!

The sword will decide for us."

Modern historians have had understandable difficulties in trying to decipher the realities of the Battle of Kosovo. They have had to sift through a myriad of often rhapsodic and idealized, mostly apologetical, renditions of relevant decisions and events. Contemporary chroniclers, and later a lot of biographers and "history writers," as a rule, had to keep in mind the interest of their protectors and sponsors, with objectivity not always their trademark. The casual author, for instance, thought nothing of reviving King Vukasin (18 years after his death) to bring him to Kosovo as a participant, with "his 30,000 troops." Groping through all this poetic license was unavoidable. But to the credit of epic writers, many of them provided data that were later corroborated by more reliable sources.

It is quite certain that Prince Lazar must have held some kind of war council with his vojvodas on the eve of the battle. Some among those present must have had apprehensions about Serbian prospects, especially in the light of the hesitancy, lukewarm enthusiasm, and even disloyalty among some Serbian warriors. Prince Lazar could easily have agreed with the evaluation which a national bard put into the mouth of Vuk Brankovic: "Fight we may, but conquer we cannot ..." Lazar could also have believed that some of his vojvodas were seriously thinking of passing over to the camp of the sultan, among them Milos Obilic, who was seen conferring with two other commanders and inquiring about Turkish battle deployment.

On the eve preceding the day of the battle, Prince Lazar, according to the Chronicle of Monk Pahomije, asked for a golden goblet of wine to be brought to him. In his toast he mentioned 3 brave and dashing vojvodas as possible traitors, who were "thinking of deserting me and going over to the Turkish side." These 3 were Ivan Kosancic, Milan of Toplica, and Milos Obilic. Prince Lazar appealed to Milos not to betray him, and

drank a toast to him: "Do not be faithless, and take this golden cup from me as a souvenir." Milos responded with a few words of noble

indignation: "Oh Tsar, treachery now sits alongside your knee," an allusion that Vuk Brankovic was responsible for this lack of confidence. This scene on the eve of the battle reminds one very much of the Christian saga of the Last Supper, where Lazar emerges as a person similar to Christ, knows very well the inevitability of treachery among humans, as well as knowing his own fate. Lazar behaved as a good Christian should, and had no rancor even toward those who failed him.

As for Milos, he too behaved as a gallant Christian: "For thy goblet I thank you, For thy speech, Tsar Lazar, I thank you not ... Tomorrow, in the Battle of Kosovo, I will perish fighting for the Christian faith."

It is indeed interesting that the Romanized West never saw Lazar and Milos, and their likes of Serbian Orthodoxy, as fighters for Christianity. It is well to recall, however, that before going into battle, Lazar left the Serbian people the famous statement, which they have eternally treasured and which is the essence of the Gospel Message:

"The Earthly Kingdom is short-lived, but the Heavenly One is forever."

As for the Kosovo Battle, all available information seems to confirm that Murad succeeded in surprising the Serbian army, as he had done at Marica in 1371. In accordance with the advice of his commander Evrenos Bey (of Greek origin), he launched his attack early in the morning while Lazar and his comrades were at prayers in the nearby Samodreza Church. It was there that news reached him that the enemy was already attacking his front lines. It was there, also, that he was informed that Milos and his two godbrothers, Ivan and Milan, had been seen riding out in the early dawn toward the Turkish lines. This must have strengthened his belief that the three vojvodas were indeed traitors, and that Vuk Brankovic was right when he expressed doubts about Milos. He must have thought of the summons he had sent to all Serbs before the battle,

which, according to national tradition reads: "Whoever born of Serbian blood or kin comes not to fight the Turks at Kosovo, to him never son or daughter born, no child to heir his land or bear his name. For him no grape grow red, no corn grow white, in his hand nothing prosper. May he live alone, unloved, and die unmourned, alone!"

As Lazar blessed his soldiers, he led them into battle, the clash that was to decide the fate of Balkan Eastern Orthodox nations for a long period to come. The Turkish historian Neshri describes the first phase of the battle in the following words:

"The archers of the faithful shot their arrows from both sides. Numerous Serbians stood as if they were mountains of iron. When the rain of arrows was a little too sharp for them, they began to move, and it seemed as if the waves of the Black Sea were making noise ... Suddenly the infidels stormed against the archers of the left wing, attacked them in the front, and, having divided their ranks, pushed them back. The infidels destroyed also the regiment ... that stood behind the left wing ... Thus the Serbians pushed back the whole left wing, and when the confounding news of this disaster was spread among the Turks they became very low-spirited ... Bayazet, with the right wing, was as little moved as the mountain on the right of his position (Kopaonik). But he saw that very little was wanting to lose the sultan's whole army."

But the quick thinking and decisiveness of the sultan's son turned the flow of the battle. Among the Turks he was known as "Ildarin" (Lightning). He attacked the flank of the advancing Serbian force, and succeeded in repulsing and throwing into considerable disarray the hitherto victorious Christians. At that critical moment, a Serbian corps of some 12,000 cuirassiers was withdrawn from the battle by their commander, Vuk Brankovic. He apparently either lost his nerve or thought it inadvisable to lose all of his men in a futile battle. But Lazar was of a different disposition. He tried to rally his disheartened troops around him, and led them into a new attack, which failed. Inevitably, the morale of the Serbs plummeted. Wounded, Lazar was taken prisoner, and his army, rapidly falling apart, was beaten and dispersed on the early afternoon of that very day.

Serbian chroniclers maintain that, as he was led to Murad's tent, Lazar saw the wounded Vojvoda Milos there, and only then realized what heroic deed he had done. Deeply touched, Lazar gave Milos his blessing, as he realized that Milos had mortally wounded the sultan, striking him in the abdomen with a concealed dagger. Milos got access to Murad's tent by pretending he had come to surrender and wanted to kiss the sultan's foot.

There they were, in that tent, all the featured actors of the Kosovo drama, ready for the final Shakespearean resolution of the plot. One of Murad's close advisers (Ali Pasha) lay dead already; he, too, a victim of Milos' dagger. Prince Bayazet ordered Lazar and his nobles executed by the sword, in the presence of the dying sultan. The Serbian nobles asked to be beheaded first. Bayazet turned down their plea. But when one of Lazar's vojvodas, Krajimir of Toplica, asked for permission to hold his own robe so that Lazar's head would not fall to the bare ground, Bayazet, impressed by such loyalty, granted the request. Milos Obilic was beheaded first. As Lazar started to say a few last words to his nobles, he was abruptly stopped by the Turks. Kneeling, he could only utter: "My God, receive my soul."

Murad lived long enough to see his enemies beheaded. As he died, his younger son Bayazet made sure immediately to eliminate his brother, Jacub, who had also taken part in the battle, and thus assure his ascendance to the highest position as head of the victorious Turks. Moreover, he took Lazar's daughter Olivera into his harem and led the Turks in other battles. The Serbian princess must have meant a lot to the Turk called Lightning, because when 13 years later he was taken prisoner by the leader of the Tartars (Tamerlane), Bayazet chose poison rather than watch the jewel of his harem, Olivera, serve her new master.

As Vidovdan 1389 came to a close and the sun went down behind the mountains of Zeta (Montenegro) in the west, the night that would last 5 centuries began. Both in their 60's, 2 tsars lay dead on the plain of Kosovo, surrounded by their slain brave warriors. Murad's body was carried by his warriors all the way to Asia Minor, to the city of Broussa. Present at the burial ceremony were 2 Serbian vojvodas, the ones that were ordered by Bayazet to escort the body of their enemy. Today, the visiting tourist is told that the 2 sarcophaguses, next to Murad's contain the "bodies of unknown decapitated Serbian nobles."

By the grace of the new Turkish sultan, the Serbs were allowed to pick up the severed head of their leader and carry it together with the body to the Church of Vaznesenje Hristovo in Pristina. Later the remains were moved to the Monastery of Ravanica. The Serbian Church proclaimed Prince Lazar a saint and holy martyr. The mutilated body of the saint prince could not, however, rest long in his native land. As the Turks moved to the north, his remains were carried to Fruska Gora (Vrdnik Monastery) in Srem, at that time in Hungary. The wandering bones had to be moved a fourth time, when in 1941 the Croatian Ustashi began pillaging Serbian holy places in the newly created Axis satellite, the Independent State of Croatia. Tsar Lazar's relics were taken to Belgrade for safe keeping, to rest in front of the altar of the main Orthodox cathedral where current generations have had an opportunity to view and honor Lazar's shrunken body in the robe of faded red and gold brocade, a dark cloth hiding his head and the gap between it and his shoulders. In 1989 the body of Prince Lazar was returned to the Monastery of Ravanica near Cuprija, built by Prince Lazar. For the Serbs, Kosovo became a symbol of steadfast courage and sacrifice for honor, much as the Alamo for Americans - only Kosovo was the Alamo writ large, where Serbs lost their whole nation, but in the words of Sam Houston, it would be "remembered" and avenged.

|