Kosovo

by William Dorich

Kosovo

by William Dorich

|

|

Alex Dragnich and Slavko Todorovich

Raska and Kosovo

Visiting the territories of former Rascia (Raska) and Kosovo, one encounters many visible landmarks that are witnesses to Serbia's medieval grandeur. An extensive discussion of these art monuments is beyond the scope of this study. Rather, in this brief chapter some of the surviving monuments will be examined as documents of Serbia's cultural legacy in Kosovo and adjoining areas .

Visiting the territories of former Rascia (Raska) and Kosovo, one encounters many visible landmarks that are witnesses to Serbia's medieval grandeur. An extensive discussion of these art monuments is beyond the scope of this study. Rather, in this brief chapter some of the surviving monuments will be examined as documents of Serbia's cultural legacy in Kosovo and adjoining areas .

Serbia's (Raska's) opportunity to firmly establish its cultural presence in the Byzantine-dominated Balkans came with Serbia's methodical consolidation of her rise as a political power under a single and powerful leader. This evolution in Serbia's medieval history was particularly active in the latter half of the 12th century, when the Latin West, led by the Venetians, struck against Byzantium during the Fourth Crusade and finally sacked Constantinople in 1204. Serbia was thus presented with circumstances favorable to the advance of its own political and religious cause, due in no small part to the divisions within the Byzantine Empire, divisions that lasted until the restoration of the empire in 1261 under the Palaeologan dynasty.

Nemanja, the founder of Serbian medieval statehood, deserves the credit for not missing the chance to advance the Serbian cause politically, and his son Sava was equally responsible for expanding Serbia in the realm of culture and art. Nemanja was certainly aware of the need for a strong Serbian political unit that required cultural manifestations that could easily be identified with the Serbian people. The choice of Sava to implement these political and cultural plans was not accidental. As a politically astute leader, Nemanja knew that the great centers of Constantinople and Thessalonika in the east, and his own Zeta littoral in the west, were culturally rich but stylistically diverse regions. Byzantium abounded in artists of every kind, while the coast of Zeta provided stone masons of unparalleled skills. But it was only under the generous patronage of the members of the Nemanjic dynasty, and above all under the sage and brilliant guidance of Sava, that these two different artistic outlooks could be united to produce from old tradition-bound forms new and creative combinations that could easily be identified as the art style of Raska.

Sava, a Mount Athos monk, scholar, and theologian trained in Hilandar Monastery, was eminently prepared to build the foundations upon which a national culture would grow within the religious environment of Eastern Orthodoxy. As a man of his time, a diplomat above all, serving his newly-born state, he had the opportunity to know most of the leading figures of the era - from emperors sitting on the various thrones of segmented Byzantium to the heads of Churches and spiritual leaders of monastic communities from Nicaea and Jerusalem to the shores of the Adriatic and beyond. In his travels he became acquainted with architecture and religious art in the churches and monasteries throughout Byzantium and all the way to the Holy Land.

Sava learned from the treasured stores of knowledge safeguarded in monastic libraries. He must have known personally many of his contemporary learned authors and theologians, either as friends or adversaries. He was able to commission from Constantinople works by some of the most outstanding painters of that period. Never again in its history would Serbia have a son of his stature and impact. He was the youngest member of the family, whose father was to follow in his footsteps as a monk, and whose ruling brothers would listen to and heed his advice.

Abroad, the Byzantines were distrustful of him (the Greek archbishop of neighboring Ohrid anathematized him when he succeeded in gaining autocephaly for the Serbian Church), but still needed him. The Bulgarians revered him, while the papal alliance avoided dealing with him.

When the Byzantines and the Latins were dividing the Balkans, Sava made sure that the dividing line did not go through Rascia. He was determined to withstand Roman Catholic religious pressures, and to establish Orthodoxy as a national faith, and through translated liturgical services to give it a Serbian character.

These unique geo-political circumstances had a lasting impact upon the evolving Serbian cultural manifestations, the surviving remains of which can readily be seen not only in the former lands of Raska and Kosovo, but even and beyond Nemanja, who did not want to be remembered by castles or fortresses but by churches, and Sava proved to be a magnificent combination: a pragmatic father to construct a viable frame and a sophisticated and artistically sensitive son to fill it with relevant content. Above all, Nemanja and Sava set a precedent to be followed by the other members of the Nemanjic dynasty, their noblemen, and high clergy - the end result being untold artistic and cultural riches, the pride of the Serbian nation to this very day.

One of the early structures sponsored by Nemanja was dedicated to a military saint, Saint George, and placed as a proud symbol on a tall promontory overlooking Nemanja's capital city of Ras. It was a single nave, domed structure and its twin-towered entrance gave it the popular name Djurdjevi Stupovi (1170-1171). This church was sumptuously decorated (1175) by an outstanding but anonymous artist. Due to military and other calamities, the frescoes survived only in small fragments (recently the structure was restored and roofed). In spite of the losses of painted surfaces, the entire iconographic schema is clear - a lower zone of standing saints; two zones of compositions from the life of Christ; and in the dome the image of the Lord in bust.

An addition to the painted program of Djurdjevi Stupovi was provided by Nemanja's great grandson, King Dragutin in 1282-1283. Most interesting for Serbian history is the painted program of the ground floor chapel, under the entrance tower, created as a burial place for Dragutin himself. Here one sees the members of the Nemanjic dynasty, from founder onward (with their wives) in ceremonial procession approaching the Enthroned Christ. In the groin vault covering this chapel there can be seen, as a permanent document for posterity, four illustrated events: Nemanja as Monk Simeon relinquishing his throne in favor of his son Stefan; the enthronement of Uros I as king of Serbia; Dragutin's assumption of the throne; and finally, his relinquishing the throne in favor of his brother Milutin.

Nemanja's laying of religious foundations was more than an artistic endeavor. It served political and religious purposes, but it was above all aimed at the salvation of his soul. To house his own crypt, Nemanja built a monastery (1183-1191), well-hidden in the canyon of a swift tributary of the Ibar River, to which he gave the name Studenitsa. It is to this site that Nemanja withdrew from ruling duties to become Monk Simeon, living there for over a year and a half before going to Mount Athos.

The Church of the Virgin, the center of this monastic complex, later served as a prototype for several other churches destined to be burial places of Serbian kings. While the frescoes in the church are typically Byzantine and the marble portals and their sculptures and reliefs Romanesque, the parts taken together bear the imprint of the Serbian spirit. After the transfer of Nemanja's remains from Mount Athos to Studenitsa, Byzantine painters were engaged to decorate the walls of the church (1209). Most likely, Sava helped plan the iconographic program, and most certainly gave instructions about historical personages to be included. Although the painter left an inscription in Greek at the base of the dome (now only partially preserved), all other inscriptions throughout the church are in Serbian, written in large and beautifully formalized letters, undoubtedly under the explicit influence of Sava or perhaps by his own hand.

To the original church a large outer narthex was added in 1235. Here, too, fragments of fresco paintings are preserved. Among the more significant ones are those in the south chapel, where one finds the oldest preserved historical compositions with specifically Serbian subjects, which together with the religious scenes indicate that they were inspired directly by Sava's writing. The historical events deal with the transfer of Simeon's relics from Mount Athos to Studenitsa. Also present are the dynastic portraits, from the founder to King Radoslav carrying the model, indicating that he was the donor of this addition to the Church of the Virgin.

To the south of the church stands a much smaller structure, the so-called King's Church, built by Nemanja's great grandson, King Stefan Milutin. This powerful and wealthy ruler of Serbia for almost forty years reputedly built or renovated a church for every year of his reign. Some say that this number is exaggerated, but the numerous religious structures still standing throughout Serbian lands, and even reaching to Jerusalem and Constantinople, are historical testimony to King Milutin's generosity.

The King's Church, with a small, single nave and domed, was decorated in or around the year 1314. The total iconographic program is relatively well-preserved. In the opinion of scholars, the quality of the preserved frescoes is the best of this period outside Constantinople. Besides representations of the twelve liturgical feasts, saints and prophets, and cycles from the life of Christ, there are dynastic portraits from Nemanja and Sava to King Milutin (holding a model of the chapel) and his child queen, Byzantine Palaeologan Princess Simonida. Although this tiny monument endured much destruction over the centuries, a part of the king's inscription remains and reads: "... whoever alter this let him be cursed by God and sinful me, amen." The long dead king still seems to be guarding the small foundation.

Following the example of the founder of the dynasty, the sons, grandsons, and other descendants continued building churches throughout Serbian-held lands. All of these structures, with their plans, elevations, and artistic embellishments, are grouped together into a stylistic unit known as the Raska School, being distinctly different from other Serbian schools, such as the Morava School to the east and the Zeta School to the west. Raska and Kosovo were at that time a single political and cultural entity. As all things in medieval society, churches had their hierarchical order. Famous and venerated as it was, the Studenitsa Monastery was not the first-ranked church among Serbian-built religious structures, since it was not planned as the see of a Serbian archbishop.

The Church of the Ascension of Christ in the Zhicha Monastery, built by Sava and his brother Stefan (after 1207), was perceived as the "Mother of Serbian Churches," and eventually became the coronation church of Serbian kings, beginning with Stefan the First Crowned. As mentioned by Sava's biographer, Theodosius, Sava brought with him the builders and marble workers "from the Greek land." For the painted decoration of this church, executed about 1220, Sava brought painters directly from Constantinople.

It is surprising that Sava, who took care of the planning and execution of so many of the early Nemanja structures, did not build his own resting place. Nemanja's grandson, King Vladislav, buried Sava in the famous church of the Ascension of Christ in his own Mileseva Monastery. This domed building of the Raska style was erected near Prijepolje probably just before the year 1230. At that time it was decorated with frescoes, whose artists tried to emulate the noted Byzantine mosaic technique. From this church comes some of the most beautifully painted images that have been preserved in the entire corpus of Serbian medieval paintings. Among them is the elegant and serene figure of the Virgin from the Annunciation.

In 1236, King Vladislav brought the body of his venerated uncle to this church. Sava died in Trnovo (Bulgaria) a year earlier, while on yet another diplomatic mission, this time successfully to negotiate autocephalic status for the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. It was a difficult task for the Serbian king to bring Sava's body to his native land. Sava was so venerated in Bulgaria that Vladislav's father-in-law, the "fearless" Tsar Asen II, lacked the courage to let Sava's earthly remains be taken out of the country, fearing the rage of the local population. Some popular tradition has it that Vladislav literally stole the body of his uncle and brought it to Mileseva. Actually, he had permission from the tsar, but to avoid possible incidents the body was removed secretly. Some years later, Vladislav was also buried there.

The tomb of Sava, the first Serbian archbishop, became one of the venerated places for the Serbs. Even after his death, he had a special role in the life of his nation and its rulers. In the 14th century, Bosnian King Tvrtko I crowned himself king of Serbia on Sava's grave, an act obviously full of significance. Another nobleman, Stjepan Vukchich, assumed on the tomb of Sava the title of "Herceg [heir] of Saint Sava."

The Turks burned Mileseva in 1459, but the church building survived. Some 150 years later, the Islamized Albanian from Prizren, Grand Vizier Sinnan Pasha, campaigning in Hungary and dissatisfied with the behavior of Serbian homesteaders, ordered Sava's body disinterred and burned on a pyre in the Vrachar area of Belgrade. The Serbian Orthodox Church declared this youngest son of Nemanja a national saint.

In the period between 1544-1557, the Mileseva Monastery became a "publishing house," printing on its own presses numerous liturgical books. The popularity of these productions among the Slavs was considerable, and some reached as far as Russia. In return, some gifts were sent from Russia to the monastery. For example, still preserved in the monastic treasury is a chalice donated by Tsar Ivan the Terrible in 1558. Mileseva had its own school where Serbian children learned to read. Among the pupils was a youngster later taken by the Turks into the janissary corps, the renowned Mehmed Pasha Sokolovich, who subsequently rose to the rank of grand vizier in Constantinople.

Twice more, in 1689 and 1782, the Turks set fire to the monastery. Its turbulent history has left its scars especially strongly on the fresco surfaces. Yet, it has one of the most beautiful and moving frescoes of Serbian medieval art, a detail of a larger composition, the "White Angel," still resplendent in its majestic presence.

Another Serbian monastery, Sopocani, was chosen by King Stefan Uros I as the site of his final resting place. Hidden among the gently rolling hills in the heartland of the Serbia of the Nemanjic dynasty, it lies near the ancient capital of Ras and the source of the river Raska. Its horizon is dominated by the above mentioned Djurdjevi Stupovi. In some ways it matched its founder's nature, a diffident and demure king, rather spartan in life philosophy and thoroughly unglamorous. Dedicated to the Trinity, Sopocani was built about the year 1265. Soon after its construction, King Uros brought the body of his father, Stefan the First Crowned, to be buried there. Subsequently, when King Uros died in exile in Hum, his body was brought to Sopocani. Also interred there is King Uros' mother, Anna Dandolo, the granddaughter of Enrico Dandolo, the doge of Venice. The death of this Serbian queen is one of the most important historical compositions preserved on the walls of Serbian medieval churches.

Architecturally. Sopocani follows the tradition of the Raska school, but the chapels used for burials make it appear as a standard three-nave basilica. Sopocani suffered greatly from natural and war disasters, partially destroying but never diminishing the beauty of its fresco decoration. Scholars are still debating the origin of Sopocani's master painters. Among them was one great but anonymous artist who painted the central area under the dome, as well as some of the standing figures. His brilliant work was among the most outstanding in all of Europe at that time.

As in Mileseva, the walls are painted in yellow, with coverings in gold leaf (now long lost) in order to emulate the mosaic technique. All of the inscriptions are in Serbian, and some of the faces of the Serbian archbishops (painted in liturgical procession in the apse) convey a feeling of the presence of living persons. Besides the religious compositions, there are numerous representations of scenes related to the Nemanjic dynasty. Many portraits of Serbian kings and their queens and princes, are seen under a benevolent image of the blessing Christ.

Earlier mention was made of King Milutin's generosity in the building of churches and monasteries. If space permitted, a discussion would be included pertaining to a number of other churches built or restored by him. One especially deserves mention, the renovated Cathedral Church of Prizren, the Virgin Ljevishka (1307). Its brilliantly painted frescoes by a group of artists who worked in Ohrid (Michael, Euthychios, and Astrapa) still fascinate the observer in spite of the damage inflicted by the Muslims when they converted the church into a mosque. Among the religious compositions and the individual images of various male and female saints, one can also see the members of the Nemanjic dynasty, from the founder in his monastic robes to the princes who went to serve the church and the nation in religious capacities, to the richly garbed King Milutin, in his splendor rivaling the Byzantine emperor himself.

In the vicinity of Kosovska Mitrovitsa, between 1313 and 1317, King Milutin renovated an older church, Banjska and dedicated it to Saint Stefan, the namesake of the founder of the Serbian dynasty and many other Serbian kings. This structure also belongs to the Raska school and was once richly decorated by sculptural carvings. Its frescoes, however, are totally lost, and the church was greatly damaged when the Turks turned it into a mosque. Nevertheless, the beauty of its polychromatic walls still testifies to the past splendor of the church, which was originally planned as King Milutin's final resting place. His royal ring is still preserved, bearing the inscription: "God help him who wears it ..."

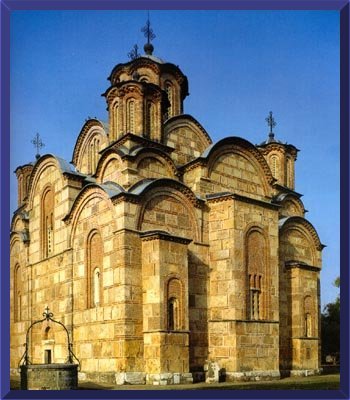

The last church built by King Milutin - Gracanica - is certainly second to none among the Serbian masterpieces. Built on Kosovo Field between 1317-1321, it was the see of the bishop of Lipljan, and ultimately it might have been planned as the final resting place of King Milutin. It is architecturally different from the previously discussed Raska school of architecture. Its master builders did not have a Romanesque stylistic orientation; rather they turned to Byzantine architecture as the source of inspiration. The church itself is a cross-in-square plan, preceded by an open narthex, and surmounted not by one, but by five domes: the central being the largest and those at the four corners being much smaller. The exterior walls show the so-called cloisonn - technique, in which stone blocks are enclosed by bricks set into the thick mortar beds. Impressive are the soaring heights of the church, and the mysteriously lit complex interior spaces, still covered in their entirety by an almost intact fresco ensemble.

Among the standing saints and Christological compositions are the scenes of the Last Judgment (covering the entire west wall) and the portraits of King Milutin and his Byzantine-born Queen Simonida, daughter of Emperor Andronikos II. The aged king and his still young queen, splendidly dressed in their bejeweled garments, are given the crown by an angel, the messenger of God. As in the case of many paintings of saints, the eyes of Queen Simonida are dug out. This event was much later immortalized in a poem by Serbian poet and diplomat Milan Rakich,

which reads in part:

"Oh, pretty image, an Albanian has dug out your eyes

With a knife when no one would see him...

But I can see, oh woeful Simonida, your long dug-out

Eyes still gleaming at me from the wall."

The names of the Gracanica painters are not known. It is a well-established fact, however, that King Milutin maintained a group of artists, whose works scholars call the Court School of King Milutin. As mentioned above, the names of some of them are known, and they came from Ohrid to work for the Serbian king. Some of these painters left their signatures on their works, thus immortalizing themselves and their royal sponsor. In the sponsorship of artists, Milutin followed the tradition of his family. His mother, Queen Jelena, supported the school for embroidery arts, and undoubtedly many a Serbian woman honed her skills there. Moreover, Milutin's brother, King Dragutin, also sponsored an art school specializing in applied arts and crafts.

Art historians in general, and Byzantinists in particular, have written volumes dealing with the style and iconography of Serbian frescoes. In general, they agree that Serbian paintings preserved on the walls of these medieval churches constitute a continuity in Byzantine artistic expression during the period when the artistic production of Constantinople was severely curtailed due to the political situation of the empire in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Most scholars also agree that Serbian art served as a link between the East and West, transmitting to Western artists, eager to learn and experiment, the venerable old tradition kept alive in the superior Byzantine technique of frescoes and mosaics, as well as style. This was the period of the 13th and 14th centuries, when Byzantium was undergoing an artistic revival (after 1261), and just as the West was on the threshold of the classical revival, self-discovery, and renaissance. The center of Serbian Orthodox Christendom was the monastic complex at Pec, most often referred to as the Patriarchate. Located in the vicinity of the rugged Rugovo pass, a nightmare to any intruder, the walled monastery conveys a feeling of remoteness in a physical and spiritual sense. The need to hide was understandable in view of the fact that Zhicha, exposed in the plains, was sacked on several occasions by the marauding Bulgarians, Mongols, and other passing invaders. Also, as the see, first of Serbian archbishops and later of Serbian patriarchs for three centuries, the monastery required seclusion. Many church dignitaries are buried there.

The complex itself consists of several churches, chapels, and a large outer narthex, all attached and forming an inseparable unit. The oldest is the Church of the Holy Apostles, built by Archbishop Arsenije in the period between 1235-1250. Some of the original frescoes are still preserved. Especially noteworthy is the majestic representation in the dome of the Ascension of Christ. To the north, Archbishop Nikodimus added the Church of Saint Demetrios during the years 1316-1324. The fresco ensemble is almost completely preserved. The images are signed in Serbian, while the painter left a signature in Greek in the apse of the church. To the south, the famous Serbian archbishop, writer, and architect, Danilo II, in 1330 added the church dedicated to the Virgin. Among its preserved frescoes are portraits of Archbishop Danilo with a model of the church, and his namesake, the Prophet Daniel.

There are other Serbian monasteries and churches (preserved or in ruins) that dot the landscape of Kosovo. Among these are Devich, Gorioch, and Lipljan. Some of these served as sources of inspiration to national bards composing verses of epic poetry, e.g. Samodrezha near Pristina, one of King Milutin's capitals.

Probably the most important of medieval Serbia's Kosovo cities was Prizren, Tsar Dushan's capital. In its vicinity Dushan provided for his final resting place the only structure that he had an opportunity to build as donor. The church was dedicated to the Holy Archangels. Erected between 1347 and 1352, it was one of the most magnificent of Serbian medieval royal foundations. Its grandeur was meant to match in every way Dushan's ambitions, particularly his planned conquest of Byzantium. The young tsar ordered the annual production of his silver mine at Novo Brdo to be set aside to cover the expenses of building and decorating his ambitious enterprise.

Although chronologically late, the style chosen was the Raska school. The exterior was purple and yellow marble blocks, while red stone was carefully selected for the interior. All of these colors had royal connotations. No expense was spared on the interior, resplendent in marble encrustations, gold leaf in vaults, silver stars, and lavish mosaics. A magnificent mosaic floor was in the process of execution when Dushan's sudden death resulted in bringing his body for burial there.

When the conquering Turks came to the region in 1455, this beautiful structure was almost completely destroyed. The conquerors ordered the building razed, and the marble blocks reused for Sinnan Pasha's mosque. The excavations between the two world wars, and after World War II, yielded a few precious fragments which attest to the church's past splendor, and some of the large foundation stones remain. In the post-World War II period, Tsar Dusan's remains were brought to Belgrade to rest in Saint Mark's Church, built in the interwar period as a large replica of Gracanica.

Besides the Cathedral Church of the Virgin of Levishka, and the ruins of Dushan's church, the Serbian royal city of Prizren still guards several national treasures, such as the Churches of Saint Nikola, Saint Mark, and the Savior, dating from the 14th century, as well as a 13th century painted cave-hermitage, the Church of Peter Korishki.

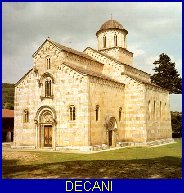

No enumeration of Serbian monasteries in Kosovo and vicinity would be complete without mentioning the majesty and serenity of the largest of all Serbian medieval churches, the Decani Monastery. It was built for King Stefan Uros III (Decanski) between 1327 and 1335. This church, too, follows the tradition of the Raska style, although there are some elements of the Gothic. The chief architect was a Franciscan from the Serbian royal city of Kotor, Fra Vita, who signed his name on one of the stone lintels. The names of the assistants are also known, the brothers Djordje, Dobroslav, and Nikola, all trained in the Kotor school. The naos frescoes were finished about 1435, the narthex only about 1450. Decani contains more than a thousand compositions, with an estimated 10,000 painted figures. There are more than twenty biblical cycles on the walls, from Genesis to the Last Judgment. This is certainly the largest surviving iconographic complex ever created within the Byzantine sphere of influence. There are royal portraits, and an immense genealogical tree of the Nemanjic dynasty. Perhaps these frescoes are too numerous to have attained the highest artistic caliber.

Tradition says that the widow of Kosovo martyr Prince Lazar, Princess Militsa, gave the monastery a giant candle to be lit only when the Kosovo defeat of 1389 was avenged. In 1913, at the conclusion of the victories in the Balkan wars, King Peter I Karadjordjevic lit that candle, signifying the liberation of Kosovo (Rebecca West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia, New York, 1982, p. 985). An eyewitness insists that King Alexander Karadjordjevic lit two candles on August 19, 1924. The body of the founder, King Stefan Decanski, who is considered a martyr among Serbs, is still resting in his church.

All of these churches and monastic establishments, the religious and artistic shrines of the Kosovo region, offer obvious testimony that Kosovo was one of the ethnically strongest Serbian territories in medieval times. The foundation charters of these monasteries are among the most reliable primary sources about the population of that period, comparable to contemporary census documents. The Decani charter, for example, lists 2,166 agricultural homesteads and 266 stock-raising properties that were deeded to the monastery. Only 44 among them can be identified as ethnically Albanian. Finally, in contrast to all of the Serbian historical monuments in Kosovo, there is not even one that is Albanian.

During the subsequent centuries, however, the ethnic picture changed dramatically. The scenes from Serbian history and the dynastic portraits of Serbian kings painted on the walls of these churches endured the flow of time. Thinned out by wars and other misfortunes, the population which venerated them did not fare so well, With these circumstances in mind, it seems appropriate to ask, could Kosovo live without a strong Serbian presence in the area? Could Kosovo continue to be immortalized through the passage of centuries only by these religious shrines and the works of art? Isolated from the people for whom they were created, are they nothing but vulnerable stones? Who brought the Albanians into Kosovo? At least some partial answers to these questions will be offered in the following pages.

|